|

My pastor delivered what I thought was an intriguing homily on the language of the Eucharist. He observed that when people talk with him about Sunday Mass, they most often tell him they attend to “receive communion.” He went on to point out the one-way or one-dimensional spirituality of Eucharist in the minds of many Catholics across the board, and that participation in the communion event is a two-way street, a clear reference to the magnificent Johannine Gospel of this summer where Jesus connects the bread of life to doing the works of his Father. The mysterious last words of the Mass in Latin, Ite missa est, actually mean “Go, it is sent,” implying very strongly that we are to leave with the Eucharist in our bodies and souls and start tackling those works of the Father. My theological training on the role of the laity in the Mass—active participation in the Mass and after it—was very similar. Action was (and remains, in most teaching texts) the dominant thrust of our lay role.

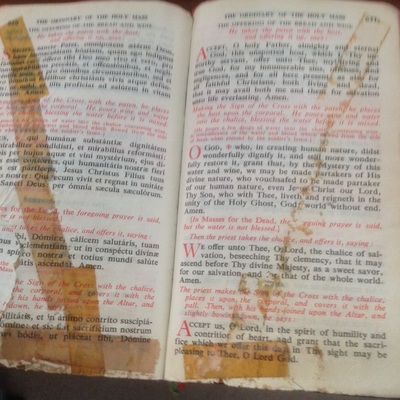

The other evening my faith group had a significant group reflection on the Eucharist, and several members expressed an aspect of Eucharistic life and worship that took a bit of a bum rap after the liturgical reforms of Vatican II, the intensely personal experience of the reception of the Eucharist and private Eucharistic devotion. Several very devout Catholics in my group expressed the intensity of returning to their pews and engaging in a profound, deep, and moving personal experience of communion with their Lord. One could argue convincingly that the very words of Jesus in Chapter 6 of St. John (“my flesh is real food”) make the case that the post-reception moments are unique, as no two people receive Christ in precisely the same way. The Mass formulary as outlined in the General Instruction of the Roman Missal, or GIRM, does make provision for at least two periods of what I would call “collective individual experience,” (1) the examination of conscience at the opening penitential rite, and (2) a period of silent prayer after the final communicant has received. (Note the GIRM instructions 84-90 which describe the sequence of the conclusion of Mass.) Interior and exterior forms of prayer can and should coexist in every sacrament. However, our tradition, quite frankly, has been shaped by centuries of a foreign language Mass in which the lay participants were in theory supportive observers of the priest offering the Mass. It became quite common for Mass attendees to engage in private devotions during Mass, such as the rosary and various litanies. The bells rung at Mass come from the tradition of alerting people to the “highlights,” such as the Consecration. Earlier popes were troubled by the disconnect between altar and pew long before Vatican II, and recommended among other things the use of a daily Missal in the vernacular for people to follow the Mass prayers as they were said, “praying the Mass.” (See picture above for my daily missal, c. 1960) In the late 1950’s there was experimentation with what was called then “the dialogue Mass.” (Wiki’s discussion of the dialogue Mass, though flagged, is surprisingly good and reliable for our needs here.) Of course, the post-Vatican II Mass of 1970 was significantly reworked to insure a full participation of the laity. But while I was in Ireland, and I did write about this here on the blog around July 3 or 4, I was struck by two things: (1) the absence of a liturgical culture; that is, much less symbolic and participatory action in the Mass, for example; and (2) a profound and personal ritual of faith that seemed to live in the Irish people I had opportunity to get to know in the countryside. The island where I was staying was losing its priest in a few weeks, and Mass would no longer be offered there. Will the Faith survive there? I think so, because it is my guess that the public Mass was never the pivotal building block in the first place, that Catholics there kept their faith in spite of the Mass and not because of it. One of the visible proofs of this is a popular religious shrine on the island of Valencia, a statue of Mary halfway up a slate mountain. My wife’s Uncle Con, I was told, walked there every day with his dog “to say his prayers.” (There is a daily miracle at this location: tour busses have never fallen off the one-lane cliff road up to the spot.) It almost seems that there is a subconscious substratum of faith among faithful Catholics there that carries the Church forward despite poor liturgy and the tragic child abuse scandals that have racked the Irish Church. This substratum of faith may very well sustain the U.S. Church, particularly in those parts of the country where Mass is infrequent and no churches are open for Eucharistic adoration. I think that the development of such an internal identity begins with the young, but in a way that touches their imaginative psyches. I had the opportunity to work on a team of play therapists, who treated abused and traumatized children as young as five by letting them act out solutions to their pain by games and play scenarios, quite successfully I might add. And, it goes without saying that our ministry and faith formation must reach that inner substratum of religious experience of adults, who know they have religious sensibilities but labor to find a name for it. Devotion to the Eucharist—in the form of the Mass, meditation, and private adoration—seems to help such believers focus upon their innermost ideals and feeds the deepest hungers. How Biblical!

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

On My Mind. Archives

July 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed