|

It’s funny how I have big gaps in my memory about the various classmates on Aroma Hill, but I can probably tell you what sport or sports each one of them enjoyed during our time at St. Joe’s. Whatever shortcomings the seminary may have had, there was no absence of participatory sports opportunities. Aroma Hill may have been situated in a remote location, but the tract of land was sizeable, enough room for farming and about a dozen sports venues of varying sizes. At various times of the year the two ventures overlapped, as fresh manure was spread over our new baseball/track and field complex every spring of my six years at the school in the hope that the sod would eventually take, which it never really did.

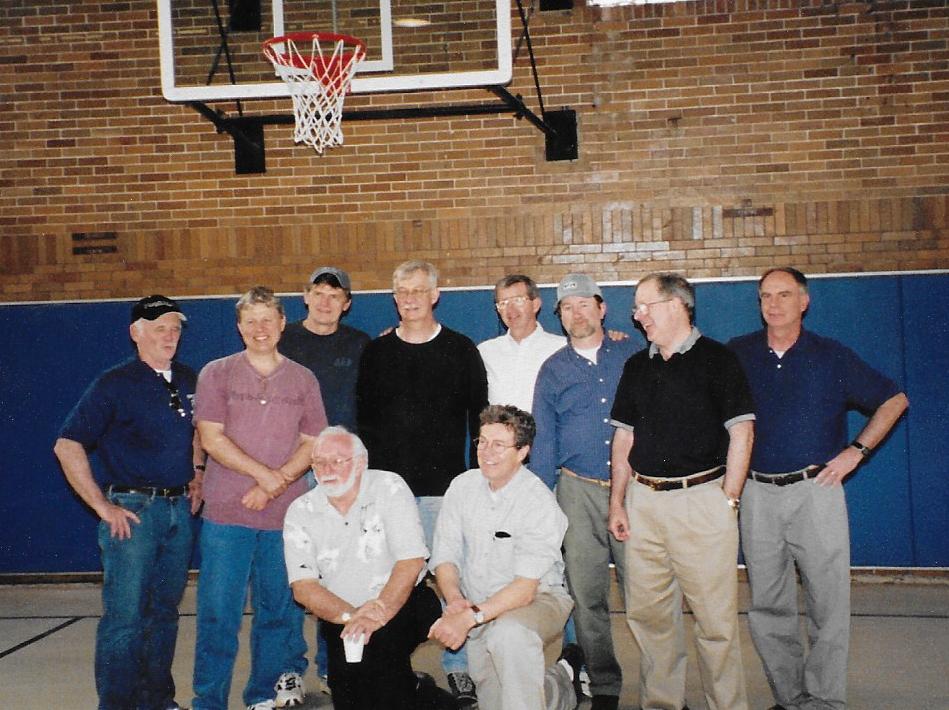

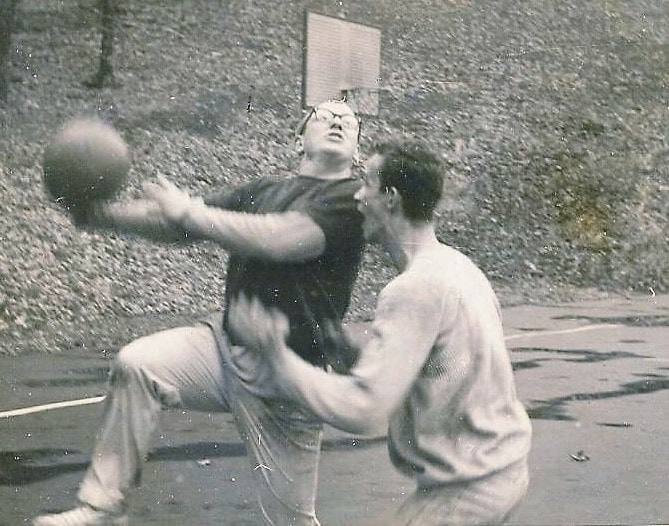

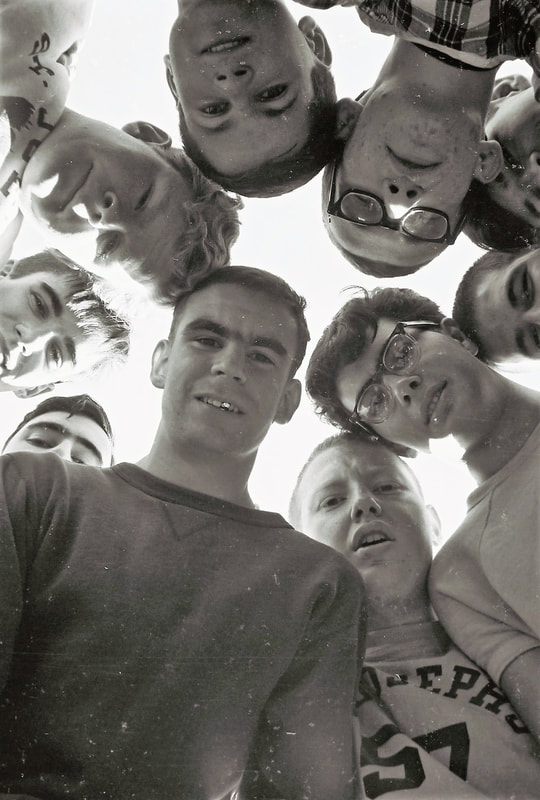

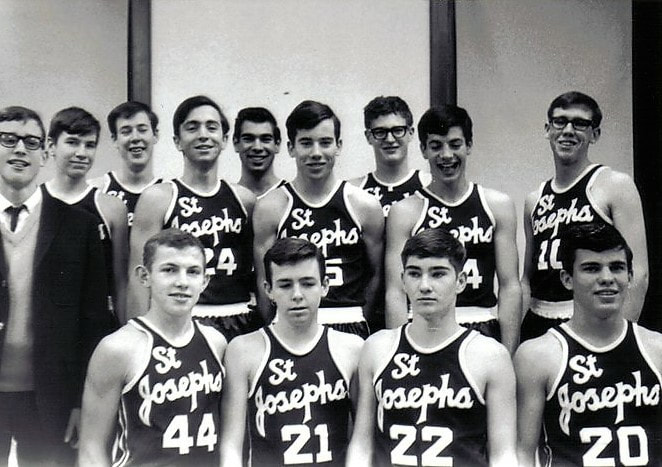

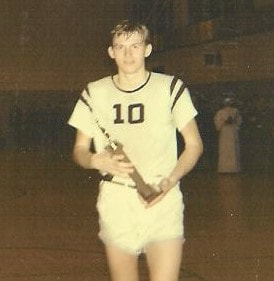

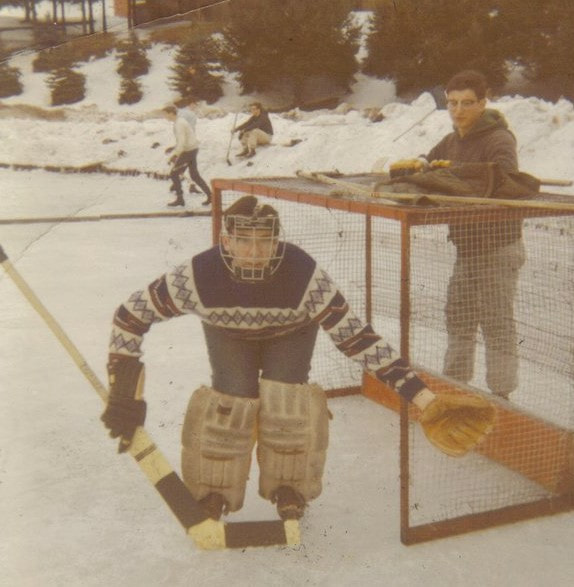

As to which was the most dominant sport in our seminary setting, I think you would get a variety of answers. Basketball was probably the most glamorous, particularly in the high school division. The varsity and JV played full schedules, home and away, against Catskill region public high schools; the toughest games were annual clashes with local powerhouses Delaware Valley and Fallsburg, along with several other minor seminaries from the Hudson Valley. Our schedules were abbreviated in the winter evening to watch the games in our cozy fieldhouse. Making the varsity was a considerable achievement, and at the risk of overkill, I would say that the high school varsity in my senior year [1965-1966] was probably the best squad I saw in my entire tenure on the hill. The fact that most of the roster consisted of my classmates, and that I am close friends today with many of them, has nothing to do with my opinion, except that they will kill me if I say otherwise. Our junior college fielded a JV team which played an eccentric schedule ranging from other JUCO’s such as Lackawanna Valley [PA] Community College to college seminaries to local prisons [away games only] and the ubiquitous Callicoon Kiwanis Club. There were intramural basketball teams as well, but with extensive indoor and outdoor courts, my memory is that pick-up games were always open and available, particularly if you didn’t mind playing on ice and snow on our black-topped courts, as we frequently did. [By the way, to one of our readers and my classmate, Father Bob Hudak—Bob, I hope your convalescence from surgery is going well. I feel very guilty for all the times I tripped you on the ice to break up an easy lay-up.] But football was a very close second. Not only were there ample places for pick-up games after school, but there were fierce class rivalries. We were not permitted to play tackle football, due to cost and liabilities, but remember that the legendary football games with President Kennedy’s family were “only” touch games, too. Somewhere in my class’s second or sophomore year we began a winning streak that extended for the rest of our seminary tenure, except for our very last game on the hill, a 7-7 tie with the college freshman class behind us. [I blame the field conditions for that outcome; punts literally died upon impact in the manure-sod.] That November 1967 game was the final college class rivalry ever played at St. Joe’s. The college division closed at the end of the 1967-68 school year. I was the starting offensive right guard for the total run of our winning streak. I was carrying a lot of weight then, and I got the position because my classmates observed how long it took defensive linemen to run around me on their way to the quarterback. The varsity baseball teams [high school and college] labored in obscurity. Our main hillside campus field was just not very good; created in 1962, it was a noble effort, but no seminary could justify the cost of professional athletic sod, and nature did not progress as hoped, though the cows certainly pitched in. If my memory holds true, we hosted our varsity games at the Callicoon village field at the bottom of Aroma Hill, at least a mile from the campus. It was difficult for students to watch the games. I tried out for the high school varsity in my junior year, and after stifling a smile, the baseball coach named me scorekeeper/equipment manager, so at least I saw the games at the small [!] expense of lugging the gear back up Aroma Hill. The high school varsity played local public schools like the basketball team, along with several seminaries. Our baseball coach, Father Brennan Connelly, whose main seminary responsibility was prefect of discipline, was very competent and stressed basic skills. There were stories that in his youth the Boston Red Sox had scouted him. In a way his coaching style resembled his spirituality of living honestly and doing the small things well. Most of our pitchers took the Greg Maddox approach of thought and control to their work. I cannot recall win-loss records over the years, but I do take away a sense of “quality experience.” One of my jobs was to phone the box scores into the Middletown Record. One day an opposing pitcher struck out sixteen St. Joe’s batters, and I got a good tongue-lashing from the sports desk of the paper because I hadn’t written down the pitcher's first name. A year after my class left Callicoon, the Record would have its biggest news story ever literally come to its front door; it was the only on-site newspaper for the 1969 Woodstock Festival and its coverage is noted in Wikipedia. [For alums, the link to the Middletown Record above will stir a lot of memories.] Also, for the historical record, I was on the college baseball roster as the emergency backup catcher in the college’s last days—an emergency being defined as an atomic war or the Second Coming. Something that might get overlooked in our memories of the Hill is the number of niche sports available to us. The high school maintained a track and field team that competed in local tournaments but also encouraged guys like me to try some things out of our comfort zone. I had my first exposure to long distance running in some of the practices, timed with an hour glass, to be sure, but I got very serious about it in college and ran daily till years after ordination. For some time, there was a boxing ring under the gym, and a decent handball court next to our “old” ball field where daily softball was played in season. No one in my time escaped a few days every year on the paved volleyball court with its grand master, our eccentric but beloved math teacher, Father Elmer. After a particularly hard math test, there was a line a mile long to get in the game and stay on his good side. There was hockey, too. I was not a skater, so my information pool is limited, but as soon as the small lake on the campus froze sufficiently, there was a modest but determined band of hockey players who scrimmaged frequently. I can’t recall if there were off-campus scrimmages or games. Once, during our high school years, Fr. Brennan decided to experiment with creating a rink on solid ground across from our dormitory. He opened several fire hoses to get the surface freezing, but the project backfired and soon water was spiraling out of the electric lights in the dorm chapel. As coach would say in his later years, “the only thing that saved me during that fiasco was that the rector was away in New York.” Not everyone engaged in contact sports, for a variety of reasons, but on Wednesday and Saturday afternoons the school gave permission to leave the campus on foot, cross the Delaware River bridge, and hike into Pennsylvania. Aside from the health benefits, it would sometimes happen that you might end up hiking with a classmate you didn’t know too well—I think the rule called for at least two guys hiking together--and at some level better communications were facilitated or old arguments reconciled. There was a remarkable absence of hubris in the “sports world” of our seminary. It was easy to acknowledge that some of my classmates were truly gifted, but none of them ever acted “elite;” for me, at least, they were always part of the guys. In fact, they were generous with their time and skills. One versatile pitcher taught me how to try to catch a knuckleball. But in the “greatest love no man hath” department, honorable mention goes one of my closest friends today, a classmate and starting pitcher in high school and college. It was an early spring day, cold, damp, and miserable, and we were just loosening up on our manure/sod infield. No one was using the mound, so I asked him: “I have never actually pitched from a true pitcher’s mound. Do you mind catching me for a few minutes so I can feel what it’s like?” He readily agreed and put on basic catcher’s equipment [wise man] while I took the mound. I had no formal training on baseball grip, so I just reared back and fired one in with all my might. I delivered a 58’ “fastball;” unfortunately, home plate is 60.5’ from the mound. My pitch kicked up a hail of manure, sod and mud, right into his face. As he was cleaning himself off, he casually remarked, “I read somewhere that a ball has to go at least 50 mph to reach the plate.” I ran in to the plate and said that one pitch was all I needed. My “second pitch” was much better: a few years later, when we got to Washington, I suggested he and I go out drinking at the Catholic University Rathskeller for Halloween Night. Wouldn’t you know, he met his future wife on our outing. For those from St. Joe’s who would like to add or subtract from my limited accounts here, the best place may be the “St. Joe’s Reunions” site on Facebook, or at the response site below:

0 Comments

In 1962 the general Catholic population knew at least two things about seminaries, local or boarding facilities: no girls, and Latin. At St. Joseph’s Seminary in Callicoon, N.Y., it was a bit more complicated. No girls, to be sure. And there was Latin. But there was also Greek. There was also French. And, if you count English as well, you have the recipe for my high school class’s senior year, where four of our seven periods were languages. The darn thing is, I never mastered any of the foreign three, and many would say that my English ain’t too good, either.

I have no access to student records aside from my own, and some anecdotal conversations, but it was my impression that at least several very good young men were asked to leave the class which entered in 1962 because of their difficulties with classical languages [Latin and Greek]. The irony is that the Council Vatican II, in its 1963 decree Sacrosanctum Concilium, opened the door to the return of worship in the native tongue, meaning that the primary reason for studying Latin, its use at daily Mass and the other sacraments, was evaporating with each year of our studies. But the bureaucratic wheels grind slowly, particularly at the Vatican. I am going to throw out a quote to see if you can identify its author and the year of composition: “There can be no doubt as to the formative and educational value either of the language of the Romans or of great literature generally. It is a most effective training for the pliant minds of youth. It exercises, matures and perfects the principal faculties of mind and spirit. It sharpens the wits and gives keenness of judgment. It helps the young mind to grasp things accurately and develop a true sense of values. It is also a means for teaching highly intelligent thought and speech.” I was surprised as much as anyone to learn that this quote comes from Pope John XXIII, the pope with the reputation for changing everything. It appears in the encyclical Veterum Sapientia and reaffirms earlier popes’ instructions that [major] seminary courses be conducted in Latin. Years later I asked an old-time instructor from Christ the King Seminary, then in Olean, N.Y., if he had really taught in Latin at this major seminary. “Well, it was a funny thing. Every now and then the rector would get scrupulous and tell us to stop using English and go back to Latin. But none of us could speak it well, and the students complained, and soon enough we were back to English explaining Latin texts.” The date of issue of Veterum Sapientia, incidentally, was February 22, 1962, seven months before the opening of Vatican II and six months before my class entered St. Joseph’s. Vatican II or not, Latin was still a blue-chip stock when we entered, and we would be heavy investors for six years. The first or freshman year of our linguistic crusade began with a general introduction to elementary Latin grammar and vocabulary, and perhaps a few simple paragraphs to stick our toes in the water. The next fall, our sophomore year, plunged us into Julius Caesar’s Commentāriī dē Bellō Gallicō, or Commentaries on the Gallic Wars in the area of 60 B.C. The first sentence of this collection begins with the deceptively simple “Gaul is a whole divided into three parts,” Gallia est omnis divisa in partes tres,” which was the last simple sentence we would ever see in our careers. This was also the last Latin sentence I would ever see where the verb is not the last word of that sentence. Our teacher was reasonably competent if not particularly enthusiastic—he was waiting for an assignment to the missions--and the course was something of a military chore. Junior year brought us to the writings of Cicero. I turned 17 that year, hardly a sophisticate, and in retrospect I can see why this course was an academic washout for me. Aside from his literary artistry, Cicero’s writings were an urgent plea to preserve republican government in Rome, an effort to ward off Rome’s drift toward dictatorship under Julius Caesar and others in the century before Christ. Today, at age 71, I have some context and much interest in such concerns. But in 1964 I was not ready. I would make the comparison to a Spanish-speaking immigrant attempting to learn English by reading the Federalist Papers or the memoirs of Henry Kissinger. Academic matters were complicated as our teacher was a missionary returned to the U.S. to recover his physical and mental health. The class was irritable and restless, and the school’s academic dean took over our course in the second semester. The dean had a penchant for modesty; whenever the word rape came up in translation, he would instruct us to say, “she was deflowered.” Our senior Latin year focused upon translating the Aeneid, a Latin epic poem written shortly before Christ. The Britannica describes the Aeneid as the Roman version of Homer’s Iliad and Odyssey, which I will refer to below. Our teacher was the athletic director, much loved by most of the students, but this did not keep one of my classmates from responding to his call for a translation with a plaintive wail, “Wait a minute! Do you think I’m Superman or something?” It was this course, too, that almost killed—literally—several of us. We had options to do Aeneid-ish class projects for grades, and by this time as seniors we were living in four-man rooms. One of our roommates decided to build a Roman fort out of some flour concoction, but he had to bake it overnight. So, after night prayers, he stopped by the theater and “borrowed” a massive stage light which he mounted in his closet in teepee fashion with bare copper wires to build up enough heat to cook his fort. In the process he had accidentally coated the wires running across the bare linoleum floor with flour so that they were near invisible. We could have been killed had we stepped on the wires, which ran haphazard through the room, or maybe burned in our beds when the stage light ignited the woolen blanket wrapped around it. All for the glory of ancient Troy. In our junior year we were introduced to Greek, which as you may know already, involves memorizing a new alphabet. Having scored consistently in the 60’s in my quarterly grades, this language presented logistical problems, such as where do you find summer school offering high school Greek in your home town? Fear being the great motivator, I somehow pulled things together in late May every year to clear the finish line of 70 or thereabouts. I don’t remember who taught the courses, let alone very much about the plot lines of the Odyssey except that it took Odysseus and his men twenty years trying to get home from the Trojan War. We never attempted the first half of the epic, the Iliad, perhaps to keep our wandering minds off Helen of Troy. When I see her name today in literature, and all the troubles that surrounded her seductive beauty in Homer’s tale, I think of the late coach Vince Lombardi and his speech to the Green Bay Packers. He told the players that if any of them left the premises during the night to meet a girl, they would be fined $1000. “And if you find something out there worth $1000,” he added, “you let me know and I’ll come with you.” The bottom-line problem, at least for this linguistic genius, was lack of motivation for the language courses in general, as the faculty warned me more times than I care to remember. Did I do something wrong? Without getting too Freudian, I suspect that much of my linguistic coursework seemed disconnected from the reasons that I entered the seminary in the first place. It is worth noting that in my sophomore year of college a newly ordained friar taught the Greek course from the New Testament, particularly St. John’s Gospel, and I gained insights from that experience that I still use today. That one course taught me that even the best English translations of the Gospel do not adequately convey the theological depth of an originating language like Greek, where there are multiple ways to express Johannine teachings such as “feed upon my flesh.” I recently purchased The Rise and Fall of Adam and Eve [2017], in which the author Stephen Greenblatt contrasts the creation myth of the garden in Genesis with other creation myths, particularly those of Babylon. The term myth is often used pejoratively in everyday English, but its anthropological root is the search for ultimate truth in a culture’s self-understanding. Who are we? How did we all start? Why are we alternately heroes and villains, i.e., moral creatures? The Hebrews addressed these questions in the drama of Adam and Eve, [and Noah, for that matter] but all peoples seek to give expression to the ultimate question of “why?” in their venerable stories of origin. Most of what we labored to translate from Latin and Greek falls under the heading of myth, and much of that around the fall of a city. The little I do remember centers around the moral dilemmas surrounding the fall of Troy. Why Troy, or modern day Hislarkek, Turkey? Archaeologists believe that the Troy of Homeric epic had been destroyed six times before the war that predates David and Solomon, possibly by centuries. Why did both Greek and Latin artists and philosophers invest so much labor into preserving the memory of this war—by memorization at that--before the Odyssey was ever put to parchment? Was Troy a Grecian moral watermark along the lines of Adam and Eve in our cultural experience? I was going to exempt Cicero here from the discussion of myth, but he was an ardent spokesman for a civilization that dated its origins to the twins Romulus and Remus, believed to have been nursed and raised by wolves. Had these mysteries been laid out for us, the dots somehow connected in even a rudimentary way, would translating the classics have been the lethargic classroom exercise that I found it to be? It is impossible to say. I leave it to my classmates and fellow students on the hill to look back and make their own determinations, but given the investment of our time years ago, I doubt that no one is neutral about the experience. I ran out of time for French; I’ll come back to that in a later post. But the experience of French class in our initial sophomore year can be summed up in a daily ritual at the beginning of class. The French teacher would begin by speaking to us in French, “Prenez vos livres, a la page X,” or “Take your books and turn them to page X [the numerical page of the lesson.]” Immediately there began a three-minute disturbance as we shuffled through our texts and looked at our classmates’ desks to see if anyone had a clue of what French number he was talking about. Finally, with contempt written all over his face, the teacher would bark “175.” Every day. Nothing changed except for la page number. |

On My Mind. Archives

July 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed