|

Know where you are going...get there early...and pray for courage! Rules I try to abide by when out in the field, and yesterday I had the pleasure of spending the day with Catholic school teachers and religious education parish volunteers. My assignment was Course 101, the opening instructional day in the training and certification of our catechists and Catholic school teachers. I generally do not identify places and people on the blog, but I will tell you I was in Volusia County, FL, which has the highest incidence of shark bites in the world. Yesterday a number of very dedicated church folks, weighing the option of the Captain Quint route from "Jaws" or listening to me all day, chose the latter. And for those who have had me before, that is a very difficult decision.

I very much enjoyed yesterday's class. I liked them even better after I read their evaluations, for in their enthusiasm they overlooked my egregious short-changing of the Church documents in the curriculum. (At least I provided the internet links.) There were a number of issues raised that I haven't really addressed in the blog, and for an example I will quote one of the evaluations here: "...students come from such varied backgrounds....classroom discussions are uncomfortable or emotional because some students' comments or questions come from a very conservative family perspective while others come...from a more liberal interpretation of their faith...that is tricky!" Indeed it is, and I sometimes refer to this as the "Red State/Blue State" problem in Catholic formation. and if it is any consolation, this unfortunate division exists at every level of the Church: parish, diocese, seminary, academic, publishing. It is not particularly new though the names of the division change through the centuries. In the 1800's, those who advocated a strong papacy, who favored papal infallibility, for example, were called ultramontanes or ultramontanists, that is, those on the "other side of the Alps," specifically Italy. Intellectual Catholics on the other side of the mountain in England or France were called, well, a lot of things. In my parents' day Catholics were deeply divided over Franklin Roosevelt and later the communist scare or Joe McCarthy, himself a Catholic and graduate of Marquette University. I know that into the 21st century my parents were saying the fifth decade of the rosary every night for President Roosevelt. My Blue State parents! Many of your questions really deserve better responses than I can provide this afternoon, so I have made some notes for future entries. Among them are the Red State/Blue State divide mentioned above, the issue of what to do if you are pressed into emergency service as a school religion teacher when those inevitable reshuffles occur; what if your class is primarily non-Catholic; is there an "emergency web site" for new religion teachers; what are the best Biblical commentaries; and several others. I would like to add that our hospitality yesterday was excellent: from outdoor signage to comfortable seating to good food and hot coffee, Black cherry yogurt! Hospitality is one of the biggest assets to ministry and evangelization. I am very grateful to the parish officer who provided our hospitality yesterday; a job well done! Finally, for Diocese of Orlando readers, here is the website for the September 19, 2015 Faith Celebration Day at Bishop Moore High School as I promised yesterday. I am scheduled to present twice, on teaching the Crusades and teaching the Resurrection Narratives. But don't let that stop you.

1 Comment

I am very late today because I started my day opening a new copy of Story of a Soul, by St. Therese of Lisieux. Many of you may already know her as the young Carmelite sister who died at age 24, but left behind a work of spiritual genius, Story of a Soul, that won her a title from Pope John Paul II as Doctor of the Church.

Following the principles of my old prof, Dr. Kallina, I first examined the pedigree of the text, which in many cases is a story in itself. And sure enough the story of the text, quite apart from its meaning and content, is food enough for a daily meditation. The text I am presently balancing in my lap along with my IPad and a hot cup of Dunkin' Donuts Chocolate Donut Coffee (nowhere will this sentence ever be spontaneously replicated in English) is published by the Institute of Carmelite Studies in Washington, DC. This is the second edition of the text, released in 1996. The original is a translation by Father John Clark, undertaken in 1975, and his original introduction is included in the 1996 edition, a most useful essay in its own right. Clark, of course, is working from French renderings, which have gone through their own complicated history. For starters, one of the extraordinary facts of St. Therese is her short and secluded life: she lived in a sheltered Catholic home till the age of 15, then in the convent for nine years till her death. On the face of it, why would anyone care what this nondescript novice had to say about anything? Does the nature of the text itself answer this question? Clark discusses both the texts and the way they were "promoted" so to speak. There are in truth three versions of "Journey of a Soul." The first, "A," is an autobiographical sketch written by the saint under obedience by her superior; Therese gave a copy book to the superior as a gift. This first manuscript concluded with her entrance into the convent. The second or "B" manuscript was written at the request of Sister Marie of the Sacred Heart (her spiritual director?) who expressly wishes the saint to expound her "little doctrine" in the older woman's terms. Clark observes that by this time Therese was experiencing significant symptoms of the disease that would ultimately kill her. The "C" document is a tribute to "feminine diplomacy," as Clarke puts it. Therese's original superior regretted that the original autobiography (A) had ended with entrance into the convent without any description of her years in religious life. No longer having authority over the author, the former superior began a gentle but persistent campaign to have the general superior put Therese under obedience to include her convent years. Therese was by this time seriously ill, and finishing the work was itself a heroic act. It was only around this juncture that Therese had any real sense that her writing might have a life of its own after her death, and she felt that her own expression was perhaps inadequate. She asked her sister Pauline to edit her writing, giving her the power to make editorial changes, including addition and subtraction. After her death, Pauline asked permission to have all three manuscripts published (Pauline herself was a Carmelite nun), and the Mother Prioress agreed on the condition that the texts be unified to read as one outpouring of Therese's soul...to Mother Prioress. From a literary vantage point, Clark commends Pauline's redaction as an excellent work. For a decade the writing was presented in this form, but when formal investigation of the sister's life for possible sainthood began in 1910, the Roman auditors ordered that the true subjects of Therese's writing be made public for future publication. The news of this led historians of the early twentieth century to seek the original texts from Therese's hand, as their profession would demand. The originals did exist, and the Carmelite community did try to allow her family (that is, Therese's natural family members in the Community) to do the editing, after being ordered to do so by the Church in 1947. Pauline was the natural choice, but now in her 80's she was the first of many to discover that the manuscripts were without paragraph divisions, pagination, etc. Eventually the work was undertaken by a Father Francois, who reproduced Therese's texts precisely as the saint had produced them. The finished work was so stark--and unlike the Therese remembered by her Order--that a new French edition was commissioned "to meet the needs of the ordinary person" as the preface reads. The translation was completed in 1972. Clark's English translation of the new French edition was completed in 1975 and made possible the wonders of the saint's spiritual insights and experiences to U.S. Catholics for the first time. Previously she had been revered as the saint who won heaven by living a very small, secluded, and unremarkable life. It turns out she had much to say after all. I am not attending Mass in my home parish weekend, as we are heading out to our diocesan retreat center this afternoon for a Mass and golden jubilee celebration for a religious sister with whom my wife has worked for a number of years. I got to thinking that religious order men and women celebrating golden jubilees over the next decade or so would have made first profession in the unsettled atmosphere immediately after Vatican II. Actually, a half-century ago at this time the fourth and final session of Vatican II was just about to begin. I am about halfway through the history of the Council as written by the mysterious Xavier Rynne, and it is mildly consoling to discover that there was as much humanity and disarray inside the Council as there was on the outside, the church of everyday.

I was simply professed in 1969 to the Franciscan Order, and solemnly professed in 1972 (in the midst of the severe and costly Tropical Storm Agnes.) Being a new religious in these years was interesting, to say the least. Vatican II had approved a number of reforms for religious, the primary being a return to the “spirit of the founder.” The Council did not lay down hard and fast rules about timetables, changes in apostolates or fields of work, except to say that this work should be spearheaded by the communities themselves (as opposed to being dictated by the Roman Curia) in chapters or general meetings within two or three years. With regard to the wearing of the habit, this determination was left to the orders themselves. I can remember very well that in 1968 my own province elected a Provincial or President who favored the outcome of Vatican II over another candidate who did not, by exactly one vote. One complicating factor here is that the decree on religious life was one of the last instructions to come out of the Council (December, 1965). But thanks originally to Xavier Rynne and later to the bishops themselves who gave frequent press conferences in Rome to their hometown papers (much to the dismay of the secretive Vatican Press Office) a well-read Catholic could follow the debates and learn of the straw votes within a day or two of the happening. In the United States, to be sure, and certainly in northern Europe, religious leaders began programs of reform before there was official authorization. Another thing which very much affected my own college and graduate seminary years was the fact that many of my professors had been students of the periti, the expert theologians guiding each bishop, and we as students were introduced to their thinking and books. Our American friend Xavier was a doctor of moral theology teaching in Rome. I lived in Washington from 1969 through 1974, in one of the many religious/academic houses that surrounded Catholic University. I went to class with men (and one or two women, I think) from many religious orders. I formed an impression—backed up by no reputable source besides me—that religious communities could be categorized into three groups: (1) those with pedal to the metal in experimenting with new freedoms and methods of living religious life; (2) those attempting to find a middle road between the old customs and the new; and (3) a few communities steadfastly opposed to change. My community waffled between #1 and #2, to the degree that after five years of hearing arguments about what constituted poverty in our house (orange juice with breakfast was often mentioned) I was just as happy to be moving on to ordination to the priesthood in 1974 and on to my first assignment. Looking back, it is easy to see the anguish of the men in charge. When I applied to the Vatican for laicization, I provided a list of ten such superiors, spiritual directors, professors and the like. I learned that nine of the ten had themselves left the Order and the priesthood after my ordination. We did not receive what I think most would consider a rather important part of priestly training—prayer and meditation. Moreover, since the community was generally composed of students and professors, our schedules were shaped by course times as much as anything, such that daily common Mass was not always “daily.” (This is probably not an issue in diocesan seminaries today where priestly and academic formation occur under the same roof.) Another factor of the times was adjusting to the new freedoms of the big city. In my own case, I had begun my seminary training at age 14 in a strict seminary where absence from the grounds was forbidden. This covered my high school and junior college years. The one year of novitiate was equally strict. But at age 21 I arrived in D.C. to register for my philosophy degree at Catholic University; by this time the philosophy of religious formation in my Order had turned 180 degrees toward a “full personal responsibility” approach. Were we ready to turn on a dime, so to speak? I think not, and this created a great deal of personal tension, and our mentors were agonizing along with us. Interestingly, I happened to read some significant new research within the past year on the psychosocial development of candidates for the priesthood, which indicates that today’s seminarians, like their secular peers, learn about their personal sexual being in the old “trial and error” method and well into their twenties. Formation for celibacy, virtually ignored in my training, is evidently still an area of concern fifty years later. I would be curious to know what contemporary seminary rectors are thinking along these lines. One other factor of the post Vatican II era was the deep division within the Church over its effects. There were communities within my Order deemed “unsafe” for friars in training (and even the newly ordained) because of friar hostilities toward the English Mass, concelebrating, friars’ not wearing habits, etc. This was not a problem in my Washington home, but after ordination I was assigned to a large community where a number of the friars did not speak to me, though they often spoke about me and the modern ways I said Mass. So, when I attend these jubilees at this phase of my life, I often wonder how the individual being honored was able to navigate those unpredictable waters of the early post-Vatican II era. As Mickey Mantle famously muttered after hitting a 500’ home run with a terrible hangover, “Those folks have no idea how hard that really was.” My pastor delivered what I thought was an intriguing homily on the language of the Eucharist. He observed that when people talk with him about Sunday Mass, they most often tell him they attend to “receive communion.” He went on to point out the one-way or one-dimensional spirituality of Eucharist in the minds of many Catholics across the board, and that participation in the communion event is a two-way street, a clear reference to the magnificent Johannine Gospel of this summer where Jesus connects the bread of life to doing the works of his Father. The mysterious last words of the Mass in Latin, Ite missa est, actually mean “Go, it is sent,” implying very strongly that we are to leave with the Eucharist in our bodies and souls and start tackling those works of the Father. My theological training on the role of the laity in the Mass—active participation in the Mass and after it—was very similar. Action was (and remains, in most teaching texts) the dominant thrust of our lay role.

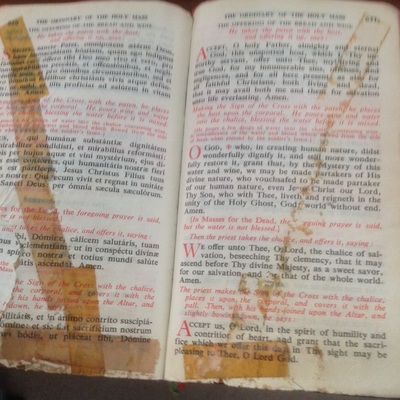

The other evening my faith group had a significant group reflection on the Eucharist, and several members expressed an aspect of Eucharistic life and worship that took a bit of a bum rap after the liturgical reforms of Vatican II, the intensely personal experience of the reception of the Eucharist and private Eucharistic devotion. Several very devout Catholics in my group expressed the intensity of returning to their pews and engaging in a profound, deep, and moving personal experience of communion with their Lord. One could argue convincingly that the very words of Jesus in Chapter 6 of St. John (“my flesh is real food”) make the case that the post-reception moments are unique, as no two people receive Christ in precisely the same way. The Mass formulary as outlined in the General Instruction of the Roman Missal, or GIRM, does make provision for at least two periods of what I would call “collective individual experience,” (1) the examination of conscience at the opening penitential rite, and (2) a period of silent prayer after the final communicant has received. (Note the GIRM instructions 84-90 which describe the sequence of the conclusion of Mass.) Interior and exterior forms of prayer can and should coexist in every sacrament. However, our tradition, quite frankly, has been shaped by centuries of a foreign language Mass in which the lay participants were in theory supportive observers of the priest offering the Mass. It became quite common for Mass attendees to engage in private devotions during Mass, such as the rosary and various litanies. The bells rung at Mass come from the tradition of alerting people to the “highlights,” such as the Consecration. Earlier popes were troubled by the disconnect between altar and pew long before Vatican II, and recommended among other things the use of a daily Missal in the vernacular for people to follow the Mass prayers as they were said, “praying the Mass.” (See picture above for my daily missal, c. 1960) In the late 1950’s there was experimentation with what was called then “the dialogue Mass.” (Wiki’s discussion of the dialogue Mass, though flagged, is surprisingly good and reliable for our needs here.) Of course, the post-Vatican II Mass of 1970 was significantly reworked to insure a full participation of the laity. But while I was in Ireland, and I did write about this here on the blog around July 3 or 4, I was struck by two things: (1) the absence of a liturgical culture; that is, much less symbolic and participatory action in the Mass, for example; and (2) a profound and personal ritual of faith that seemed to live in the Irish people I had opportunity to get to know in the countryside. The island where I was staying was losing its priest in a few weeks, and Mass would no longer be offered there. Will the Faith survive there? I think so, because it is my guess that the public Mass was never the pivotal building block in the first place, that Catholics there kept their faith in spite of the Mass and not because of it. One of the visible proofs of this is a popular religious shrine on the island of Valencia, a statue of Mary halfway up a slate mountain. My wife’s Uncle Con, I was told, walked there every day with his dog “to say his prayers.” (There is a daily miracle at this location: tour busses have never fallen off the one-lane cliff road up to the spot.) It almost seems that there is a subconscious substratum of faith among faithful Catholics there that carries the Church forward despite poor liturgy and the tragic child abuse scandals that have racked the Irish Church. This substratum of faith may very well sustain the U.S. Church, particularly in those parts of the country where Mass is infrequent and no churches are open for Eucharistic adoration. I think that the development of such an internal identity begins with the young, but in a way that touches their imaginative psyches. I had the opportunity to work on a team of play therapists, who treated abused and traumatized children as young as five by letting them act out solutions to their pain by games and play scenarios, quite successfully I might add. And, it goes without saying that our ministry and faith formation must reach that inner substratum of religious experience of adults, who know they have religious sensibilities but labor to find a name for it. Devotion to the Eucharist—in the form of the Mass, meditation, and private adoration—seems to help such believers focus upon their innermost ideals and feeds the deepest hungers. How Biblical! |

On My Mind. Archives

July 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed