|

We continue our look back at Vatican II, which concluded fifty years ago this December.

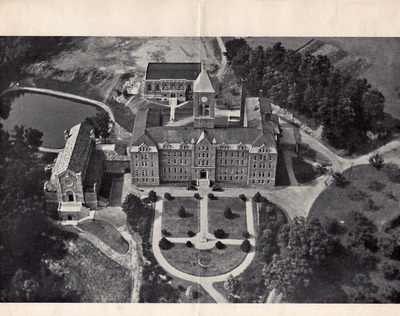

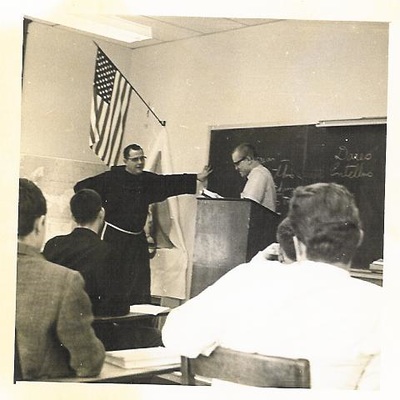

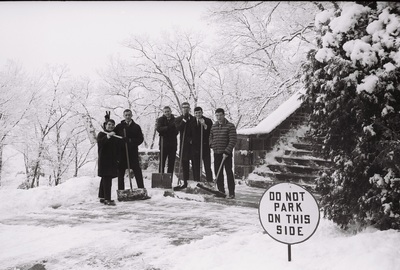

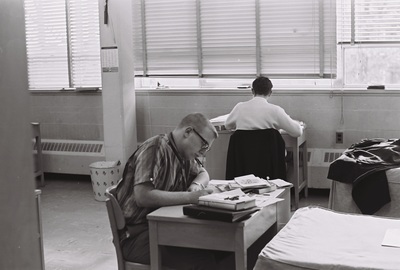

Among the documents of interest discussed in the Third Session of the Council was “Priestly Formation.” The schema was discussed from November 12 through November 17, 1964, and I bring special attention to it because of its implementation here in the United States on through the present day. Pope Francis has spoken much of the necessary qualities of bishops, which in turn has considerable impact upon the kinds of men one looks for as candidates for Holy Orders and how they are trained. Vatican II, as it turned out, was remarkably professional in its approach to seminary training, and in some ways the Church is a bit poorer today for having drifted from the Council’s plan. In his commentary Xavier Rynne expresses surprise that the first draft was as good a product as it was, and it was immediately well received by the bishops; its passage was never in doubt, possibly because the oversight of seminary training was passed to national episcopal conferences, and away from the Curial Congregation of Seminaries and Universities. The text, then, would go on to establish universal norms by which bishops would be guided in this task. The schema emphasized the importance of responsibility, proper freedom, and wider outlook among seminarians. They were expected to have what we would call today an “interdisciplinary” or liberal arts education, and specifically in the area of the study of Sacred Scripture, to understand the rudiments of last century of Biblical scholarship. Put another way, the Council was steering seminarians and their professors away from scriptural fundamentalism and “proof texting” while emphasizing the deeper theology of each of the sacred books as it had come to be understood through the twentieth century. Cardinal Leger of Montreal proclaimed the schema “a masterpiece,” and Chicago’s Cardinal Meyer welcomed the schema as a refreshing change from the stifling uniformity of seminary life still characteristic in the mid-twentieth century. A number of speakers recalled with respect the work of the Council of Trent (1545-1563) which had established the institution of seminaries in the first place as a remedy for ignorance, poor preaching, and moral apathy among the clergy. Cardinal Meyer and Archbishop Columbo of Milan both brought to the floor considerations of a new sort for public discussion, the psychological dimensions of screening and priestly formation. Rynne quotes Meyer as saying that it was not enough to train a seminarian to be a mediator between God and man, but to be a man per se. Columbo stressed personality development, lest young priests turn out to be immature, excessively passive, too detached from human society. (394) Let me pause for a moment to add that the relationship of psychology and the Church, including seminary formation, was complex in 1964. Think back a moment to the various tools of the psychological trade available then: psychoanalysis based upon the personality theories of Freud, Jung, Adler, or Carl Rogers, to name some. Freud, straight up, was at odds with the Church’s long-held views on Christian anthropology, which looked askance at a theory of inner drives of pleasure and perseverance as the ultimate dynamic of the psyche. On the other hand, long before Vatican II certain segments of Catholic pastoral work—like the Franciscan counseling and confessional ministries in downtown New York and Boston—were very sympathetic to understandings of behavioral types and mood disorders. It was not unheard of for priests to receive permission to pursue advanced degrees in psychology and even psychiatry. Discussions of psychological fitness inevitably turn to maturity, which led the Church fathers to the question of “minor seminaries.” These were junior seminaries for minor boys of 13 or 14 and above; in the U.S. these could be day schools or boarding schools; I attended the latter under the sponsorship of the Franciscans. The Council debate seems to indicate that it was the boarding school model under critique, as the Cardinal of Seville noted that “boys had a more natural and perfect seminary in their own homes.” I have been asked hundreds of times why I “chose” at 14 to pack up my worldly belongings in a trunk and move 300 miles away. The best I can say is that in 1962 there was a significant (but by no means unanimous) school of thought that if a young boy showed an inclination toward the priesthood, it was best to get him away from the temptations of the world (read: girls) as soon as possible and behind the safe walls of an isolated all-masculine environment. The word “seminary” comes from the Latin semen for seed, and we were considered at 14 as God’s little seedling vocations with the seminary as a safe and nourishing hothouse. If you throw in my year of novitiate, I lived from 14 till 21 in this environment. I’ll write more in the future about year 22, promise. (I have been able to download some old photos from the 1960's, while Vatican II was in progress, to convey the rural isolation of all of God's little seedlings up on the mountaintop. I believe there is one of me actually studying, but what else was there to do?) To be honest, by the end of the Council in 1965 the issue of finances as much as anything would determine the future of minor seminaries in the U.S. (Mine closed in 1972.) The German hierarchy noted at the Council that the Church in Germany was getting most of its vocations from among public high school graduates, finding these candidates to be more “well rounded” as it was “in the nature of man” to prefer family life. (395) Again, if one reads between the lines, the assumption is that the older the candidate, the better understanding of the implications of celibacy. Another trend developing in seminary training was the idea of expanding the educational choices, so that a candidate for the priesthood might take his philosophy and theology courses at an established reputable graduate school, Catholic University being the chief but not only example. This was particularly true of religious orders like my own; many bishops on the other hand prided themselves on their own in-house seminaries and maintained them at considerable cost. We religious order priest candidates in Washington looked down on diocesan seminaries as JV facilities issuing shaky degrees. But some dioceses, like Orlando, were sending their secular priest candidates to study under the Benedictines or other respected outside schools as late as the 1990’s. I was told by a seminary rector recently that U.S. bishops are reluctant as a rule are reluctant to send seminarians to study off the reservation, so to speak. Such are the times. Among other issues raised by the Council was finding a balance between the books and pastoral experience in seminary training. This was a serious debate in my years in major seminary (1969-74) but today it is commonplace for seminarians and deacons to live for a time in a parish getting a feeling for the realities of parochial life. Other arguments included the content of philosophy courses; the Curia argued for the philosophy of St. Thomas Aquinas, while others were more sympathetic to the modern post-Enlightenment thinkers in the classroom. Looking back at my philosophy years at Catholic University, just four years after the Council, my courses were divided between traditional Catholic formulations and some strong Avant garde material that is now passé. Not that it mattered a great deal, as we didn’t go to class very much. Remember, it was 1969, and I was in the big city for the first time. I was now 22 and Mohammed was coming down from the mountain. Comments are closed.

|

MORALITYArchives

June 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed