|

We continue our look back at Vatican II, which concluded fifty years ago this December.

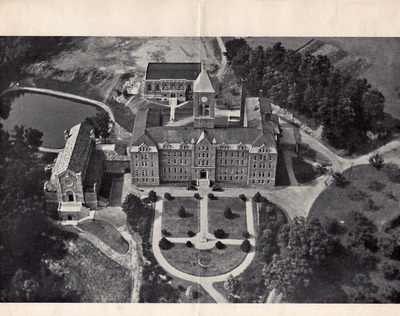

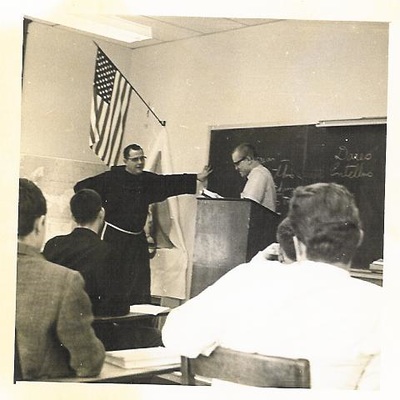

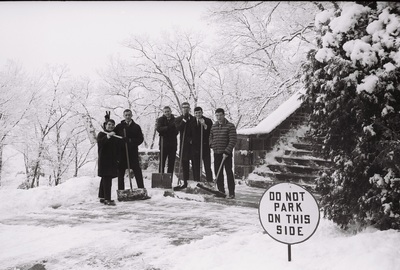

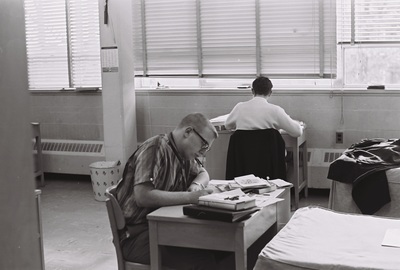

Among the documents of interest discussed in the Third Session of the Council was “Priestly Formation.” The schema was discussed from November 12 through November 17, 1964, and I bring special attention to it because of its implementation here in the United States on through the present day. Pope Francis has spoken much of the necessary qualities of bishops, which in turn has considerable impact upon the kinds of men one looks for as candidates for Holy Orders and how they are trained. Vatican II, as it turned out, was remarkably professional in its approach to seminary training, and in some ways the Church is a bit poorer today for having drifted from the Council’s plan. In his commentary Xavier Rynne expresses surprise that the first draft was as good a product as it was, and it was immediately well received by the bishops; its passage was never in doubt, possibly because the oversight of seminary training was passed to national episcopal conferences, and away from the Curial Congregation of Seminaries and Universities. The text, then, would go on to establish universal norms by which bishops would be guided in this task. The schema emphasized the importance of responsibility, proper freedom, and wider outlook among seminarians. They were expected to have what we would call today an “interdisciplinary” or liberal arts education, and specifically in the area of the study of Sacred Scripture, to understand the rudiments of last century of Biblical scholarship. Put another way, the Council was steering seminarians and their professors away from scriptural fundamentalism and “proof texting” while emphasizing the deeper theology of each of the sacred books as it had come to be understood through the twentieth century. Cardinal Leger of Montreal proclaimed the schema “a masterpiece,” and Chicago’s Cardinal Meyer welcomed the schema as a refreshing change from the stifling uniformity of seminary life still characteristic in the mid-twentieth century. A number of speakers recalled with respect the work of the Council of Trent (1545-1563) which had established the institution of seminaries in the first place as a remedy for ignorance, poor preaching, and moral apathy among the clergy. Cardinal Meyer and Archbishop Columbo of Milan both brought to the floor considerations of a new sort for public discussion, the psychological dimensions of screening and priestly formation. Rynne quotes Meyer as saying that it was not enough to train a seminarian to be a mediator between God and man, but to be a man per se. Columbo stressed personality development, lest young priests turn out to be immature, excessively passive, too detached from human society. (394) Let me pause for a moment to add that the relationship of psychology and the Church, including seminary formation, was complex in 1964. Think back a moment to the various tools of the psychological trade available then: psychoanalysis based upon the personality theories of Freud, Jung, Adler, or Carl Rogers, to name some. Freud, straight up, was at odds with the Church’s long-held views on Christian anthropology, which looked askance at a theory of inner drives of pleasure and perseverance as the ultimate dynamic of the psyche. On the other hand, long before Vatican II certain segments of Catholic pastoral work—like the Franciscan counseling and confessional ministries in downtown New York and Boston—were very sympathetic to understandings of behavioral types and mood disorders. It was not unheard of for priests to receive permission to pursue advanced degrees in psychology and even psychiatry. Discussions of psychological fitness inevitably turn to maturity, which led the Church fathers to the question of “minor seminaries.” These were junior seminaries for minor boys of 13 or 14 and above; in the U.S. these could be day schools or boarding schools; I attended the latter under the sponsorship of the Franciscans. The Council debate seems to indicate that it was the boarding school model under critique, as the Cardinal of Seville noted that “boys had a more natural and perfect seminary in their own homes.” I have been asked hundreds of times why I “chose” at 14 to pack up my worldly belongings in a trunk and move 300 miles away. The best I can say is that in 1962 there was a significant (but by no means unanimous) school of thought that if a young boy showed an inclination toward the priesthood, it was best to get him away from the temptations of the world (read: girls) as soon as possible and behind the safe walls of an isolated all-masculine environment. The word “seminary” comes from the Latin semen for seed, and we were considered at 14 as God’s little seedling vocations with the seminary as a safe and nourishing hothouse. If you throw in my year of novitiate, I lived from 14 till 21 in this environment. I’ll write more in the future about year 22, promise. (I have been able to download some old photos from the 1960's, while Vatican II was in progress, to convey the rural isolation of all of God's little seedlings up on the mountaintop. I believe there is one of me actually studying, but what else was there to do?) To be honest, by the end of the Council in 1965 the issue of finances as much as anything would determine the future of minor seminaries in the U.S. (Mine closed in 1972.) The German hierarchy noted at the Council that the Church in Germany was getting most of its vocations from among public high school graduates, finding these candidates to be more “well rounded” as it was “in the nature of man” to prefer family life. (395) Again, if one reads between the lines, the assumption is that the older the candidate, the better understanding of the implications of celibacy. Another trend developing in seminary training was the idea of expanding the educational choices, so that a candidate for the priesthood might take his philosophy and theology courses at an established reputable graduate school, Catholic University being the chief but not only example. This was particularly true of religious orders like my own; many bishops on the other hand prided themselves on their own in-house seminaries and maintained them at considerable cost. We religious order priest candidates in Washington looked down on diocesan seminaries as JV facilities issuing shaky degrees. But some dioceses, like Orlando, were sending their secular priest candidates to study under the Benedictines or other respected outside schools as late as the 1990’s. I was told by a seminary rector recently that U.S. bishops are reluctant as a rule are reluctant to send seminarians to study off the reservation, so to speak. Such are the times. Among other issues raised by the Council was finding a balance between the books and pastoral experience in seminary training. This was a serious debate in my years in major seminary (1969-74) but today it is commonplace for seminarians and deacons to live for a time in a parish getting a feeling for the realities of parochial life. Other arguments included the content of philosophy courses; the Curia argued for the philosophy of St. Thomas Aquinas, while others were more sympathetic to the modern post-Enlightenment thinkers in the classroom. Looking back at my philosophy years at Catholic University, just four years after the Council, my courses were divided between traditional Catholic formulations and some strong Avant garde material that is now passé. Not that it mattered a great deal, as we didn’t go to class very much. Remember, it was 1969, and I was in the big city for the first time. I was now 22 and Mohammed was coming down from the mountain. As I am on the road today, I was unable to post in our regular sequence. I am aiming to post tomorrow evening (Tuesday) when I reach my Thanksgiving destination. For new visitors, welcome and peruse the archives for topics of your interests. I regret that I missed posting yesterday (Sunday), and truth be told, I would much rather have lingered at the Café than what I actually did for most of the day. Recently I changed computers, financial records programs, and Windows programs at the same time. These things never go as easily as they say on the box. I did not lose anything…let’s just say I have a multi-day project of reacquainting my data bases again.

So it has been a week since I last visited the Council Vatican II. (Yesterday I was feeling very much like Cardinal Ottaviani: “all change is bad.”) We left off in October, 1964, with the heated exchange on “The Church in the Modern World.” In looking at my sources here, I note that there were other schema discussed during this time that receive less attention today but are fascinating to observe nonetheless. October 23 and 26 were devoted to the reality of atheism. Most of the Church fathers understood that atheism in the twentieth century, after two violent wars and countless other atrocities, enjoyed a certain philosophical respectability. All of us young hip collegians of the late 1960’s had our little fling with Existentialism, the post-war philosophy of human individualism and societal emptiness. The writings of Nietzsche, Jean Paul Sartre and Albert Camus sold out in every campus bookstore. Interestingly, existential atheism inspired a series of anti-establishment films like “Easy Rider,” “Cool Hand Luke,” and perhaps stretching things a bit, “The Graduate.” (Here’s to you, Mrs. Robinson.) On a more serious note, the materialistic-Marxist philosophy of communism was the professed ideology of totalitarian governments that prohibited freedom of religion, an actual threat to the Church in many parts of the world. October 26 and 27 discussed “The Church in the World,” a rambling discussion about primarily church-state relations in a world that was dividing along the “first,” “second,” and “third” worlds of the future. It was, if nothing else, an agreement that the old medieval synthesis of church and state was dead. There was a brief but historically intriguing discussion on “Racial Discrimination.” The issue of apartheid in India and Africa received particular scrutiny, and the name of Gandhi was referred to as a “magnificent example” of the kind of justice to be hoped for. Interestingly, Bishop Grutka of Gary, Indiana, observed that “it is a scandal to see parishes deserted whenever Negro families move in.” Grutka was referring to “white flight,” the move of white residents to American suburbs in a pattern that nearly all of the Rust Belt cities succumbed to after World War II, a pattern of which Detroit has become prime exhibit. Archbishop O’Boyle of Washington, D.C. recommended that racial problems be addressed across denominational lines. I am going to jump ahead to November 11 and 12, 1964, to the discussion of the schema that would ultimately be promulgated as Perfectae Caritatis, on the adaptation and renewal of religious life. As a Franciscan myself for a quarter century, this document impacted upon my life in many ways, good and troublesome. I have linked to the actual document as it was finalized in 1965, and if you have a minute or two to scan it, you will pick up a feel for the Council’s intent. Religious life (religious sisters and brothers) is rooted in the sacrament of Baptism as a state where an individual lives an intensified life of prayer and good works at the service of the Church. The “ultimate rule” of all orders is the Gospel of Jesus Christ; the specific rule of each order is the intent of the founder. Vatican II placed considerable emphasis upon a return to roots. In my youth, certainly, it was rather difficult to distinguish all the orders of nuns aside from distinctive habits. In truth, most religious sisters (except those in cloistered houses of prayer, contemplatives) were involved in the service ministries of teaching, nursing, and social work such as staffing orphanages. Most male communities evolved over time to communities of priests, and the clerical lifestyle of active pastoral responsibility tended to overshadow the simpler community style of vowed life. This occurred among the Franciscans even in St. Francis’s lifetime and was true in my years in the order till 1989. There were exceptions: I had the Christian Brothers in elementary school, an entirely lay order of men founded by St. John Baptist de la Salle in eighteenth century France. At the same time, the Council understood that religious life was badly in need of overhaul. That pre-Council women’s religious habit, so much a staple of Hollywood and Traditionalists, was actually patterned after the dress of noblewomen, as the convent or abbey was itself a place where ambitious and well-placed women of late medieval and post-Reformation times could achieve learning and influence. By the twentieth century, however, the women’s habits were endowed with different meaning—as reminders of Christ’s suffering on the cross, or to protect chastity. Perfectae Caritatis para. 17 discusses the habit in a very sane and reasonable fashion. I refer you to paras. 2, notably 3, and 8, 10, 13 and 17 where the areas of general reform are spelled out with particular relevance and clarity. There is a version of history circulated today, especially among people who never lived through that era, that PC essentially loosened the structure of religious life to the degree that it was no longer distinctive vis-à-vis the secular world, and for this reason religious women in particular left the convent in droves and caused the collapse of the Catholic school system in the U.S. This is a good example of the fallacy of post hoc ergo propter hoc, that is, if two things happen in a sequence, the second caused the first. What I would say, though, is that the main problem with Perfectae Caritatis, as is true with some other Council schemas, is that it came too late. Many young religious women entering the convent after Vatican II were not of the same cloth as the innocent Therese of Lisieux who took the veil at 15. After World War II, when dioceses like Los Angeles were opening a new Catholic school every ninety days, religious sisters went straight from novitiate to the classroom, spending each summer in college to earn a bachelor’s degree for personal and institutional accreditation. Sisters used to joke about the “twenty year plan” to earn a degree through summer school courses. In short, the typical classroom teaching religious was young, idealistic, and routinely in communion with higher education. An excellent source here is When the Sisters Said Farewell (2013); I have a review posted on the Amazon site. By the time Perfectae Caritatis was released in 1965, it is fair to say that a wholesale reevaluation of religious life was already taking place, certainly in the United States. As the French discovered centuries ago, there is no such thing as half a revolution, and through the 1960’s and 1970’s a number of painful discernments—many with extreme expressions—took place among individual religious and religious orders as a whole. The fathers at Vatican II expressed the wish for a thoughtful and gradual discernment of religious life—and a goodly number of communities embraced their recommendations, but for a large number the ways and means of reform and its consequences were already long underway. We continue our look backward on Vatican II, 1962-1965

Tuesday, October 20, 1964, is described by Xavier Rynne as “red letter day in the history of the Council.” (342) The long and anxiously awaited schema thirteen, “The Church in the Modern World,” came to the floor, a treatise on the Church’s self-understanding and its place in the parade of mankind (a Freudian analysis, albeit self-administered.) Pope Paul VI himself, as Cardinal Montini, had worked closely with Pope John XXIII and Cardinal Suenens in laying the groundwork for such a document, an implication that at the very least the role of the Church in the world was matter of discussion. This was not 1302, when Boniface VIII issued Unam Sanctam, claiming more power for Church and Pope than anyone else before or since. The significant difficulty encountered during the debate was the wide umbrella of the document’s reach. Put another way, the fathers were attempting to define in concrete language what was in large part mystery. Cardinal Meyer of Chicago, in his critique of the schema, pointed out that “13” as written seemed fearful of contagion by the world. Drawing from his Scriptural expertise the Cardinal argued for a return to St. Paul’s theology, that man’s work in the temporal order was part of the transformation that God planned for the world. Realizing that there was necessity to clearly define “church” and “world” before describing their symbiosis, several fathers recommended a closer reading of contemporary atheism, a system of meaning built entirely on worldly (or material) reality. Day Three of the debate saw a major attack on the original schema, and in truth its voice, Archbishop Heenan of Westminster, England, put his finger on what could best be called the sociological dynamic of the entire Council. Heenan complained that the schema sounded like a platter of sermons and ideas; there were many of all persuasions who felt that way. But Heenan went on to penetrating analysis of the pastoral dangers of vague documents. In so many words the Cardinal described Schema 13 as a Rorschach Test, with any person able to take away from 13 the sentiments and justifications of the subject’s persuasion. An Ecumenical Council was a new event in the lifetimes of everyone participating in Vatican II. The previous Council, Vatican I in 1870, operated under a different self-understanding of the Church; this Council decreed papal infallibility. Heenan, looking at the schema on the floor, observed that the text called upon the aid and interpretation of “experts” in the future implementation of the schema. This alarmed him: “I fear specialists when they are left to explain what the bishops meant.” He went on to deeply criticize the “specialists” [theologians] working in the Council at that time. The acrimony between the Curia and the periti or advising theologians was intense; many theologians were refused use of large Church facilities for public lectures to bishops, seminarians and the general public. A fair number were currently under investigation by the Curia as they labored away; Father Hans Kung and Father John Courtney Murray come immediately to mind. A sidebar: in his presentation Cardinal Heenan made reference to the “pill,” noting that every types were currently being tested and administered. What Cardinal Heenan had overlooked or forgotten was the contributions of famous theologians and Fathers of the Church in Church Councils and Synods, dating from Nicaea in 325 to Constance in 1415. In the latter example, this Council faced the specter of three men claiming to be pope. Under the lead of the University of Paris and other schools, the theological integrity of Councils was upheld—a good thing, because all three pretenders needed to be removed and a legitimate pontiff elected to the See of Peter. It turned out that the object of Heenan’s rage was the Redemptorist moral theologian Father Bernard Haring. Heenan and Haring would soon make up, but the English churchman’s speech did require some skillful footwork to get the Council back to the philosophical questions of “13.” The discussion turned to the thought of Teilhard de Chardin, the Jesuit paleontologist and poet who died in 1955. Chardin’s efforts to describe creation and renewal in novel and provocative images and terms led to severe censure by the Church; in 1964, however, and for some years after, appreciation of his thought made his works quite popular in my generation. Archbishop Hurley of Durban, South Africa, quoted Chardin extensively in his assessment of the greatest theological challenge to the Church, establishing the value of the natural order in its relation to man’s supernatural end. Other fathers cited Cardinal (now saint) John Henry Newman who, in the spirit of Chardin, had written in the nineteenth century that “a power of development is proof of life.” The thread of consistency in the schema 13 discussion was the admission (grudging or non-existent among some fathers) that the adjective “unchanging” could no longer be applied to the Church without qualifiers. In its best light “13” was an indication of the Church’s willingness to adopt a better language in its discourses with the modern world, where in fact most Catholics live. There was considerable agreement that the best language was service to the world and its neediest souls. Based upon the work done to date, Schema 13--those portions discussed on the floor—were approved for final redrafting on October 23 by a vote of 1579-296. It was also announced at this juncture that Pope Paul would reserve to himself, and not to the Council, a decision on the morality of artificial birth control. The Pope had previously established a committee of about 120 clerics, experts, and laity to advise him on the subject. This matter would not be formally determined until 1968, or three years after the close of the Council. For those who would like to see or peruse the final approved document on the Church in the Modern World, known simply today as ‘Gaudium et Spes’ (joy and hope), I have a link to the Vatican documents site here. We continue our Monday/Saturday reflections on Vatican II

During the discussion of Revelation in the fall of 1964, the Third Session, work was still in progress on the Collegiality schema, a detailed exposition of the unity of the pope and bishops operating together in the governance of the Church. In his opening remarks to the Third Session, Pope Paul VI had stated that episcopal [bishops’] collegiality “will certainly be what distinguishes this solemn and heroic synod in the memory of future ages.” All the same, there was a small but virulent opposition, a fair amount of it in the Curia that was managing the Council. The public position of the minority held that a statement on the importance of the college of bishops was “premature,” that it was a very recent concern of some bishops and theologians and would be a great confusion to the faithful. Part of the actual concern of the minority resembled an appeal to Einstein’s rules of physics: if the bishops get more power, the pope will have less; they seem to have overlooked the fact that the pope enjoyed his power precisely as Bishop of Rome in communion with his brethren as Peter did with the body of the Twelve. Moreover, the minority failed to recall the history of the Church. This error would come back to haunt them in a rather dramatic fashion on the floor. Even Vatican I (1870), which defined the doctrine of papal infallibility, had planned a treatment on the teaching authority of bishops as a whole, but war in Italy had caused Vatican I to disband before its other work had been done. When the full Council of Vatican II discussed the revised collegiality schema on September 21, 1964, the Curia assigned one of its own, Archbishop Pietro Parente, to present the minority position. What was unknown to about everyone at this juncture was that Parente, who had worked with and voted with the Curia through the Council, was now having second thoughts. When he took the floor, Parente stated that he was now going to speak as a bishop, and not as an officer of the Curia. He admitted that the concept of collegiality had caused “no little terror” [sic] among his colleagues who feared a diminution of papal power, and that many in the Curia had advised Pope John XXIII to avoid discussing collegiality entirely during Vatican II. But it is his theological words that carried the day: “If there is difficulty in explaining the relation between the sacred powers of the pope and those exercised by the bishops, this is not to be wondered at, since we are not dealing with a human society, but with the Church of Christ, a mystery that can only be elucidated by the theological vision of a Saint Augustine and the early Church Fathers, who adhered to the teaching of St. Paul concerning the Church as a mystical body, and thus came much closer to expressing the mind of Christ.” Parente actually accomplished three things here that shaped the future of the Council. His description of the works of the Curia was the first public verbal description of what many of the Church fathers had feared or suspected, and thus the assembled bishops felt greater confidence for future discussions. Second, Parente called into question the scholastic or systematic ways of doing theology on such matters as powers of popes and bishops. The scholastic method, or scholasticism, had ruled supreme in Catholic institutions and universities between roughly 1100-1700, and was, in fact, the operating theological method of the Curia and some of the venerable seminaries in Rome itself. Third, Parente employed a newer method of doing theology—with a much greater emphasis upon Scripture, Christology and History. In the 1960’s such a method was popularly called “the new theology” although in a number of European Catholic universities and seminaries this method had been discussed and ultimately accepted as the common method of thought and research since before 1900, though condemned by the Church, possibly to restrain anyone from doing what Archbishop Parente was doing at the Council . In our situation here, Parente was asking the bishops a simple question: do we rest our vote on the internal logic of scholastic propositions, or do we take our cue from the New Testament, the sacramental leadership models of the formative years of the Church, and the writings and leadership models of St. Augustine, for example, Church Father and bishop of Hippo in North Africa. In fairness, the debate was much more detailed, but I simplified here for the sake of clarity. On a more humorous note, when this schema came up for vote, the ballot was complex. Rynne observes that some bishops were instructed by Curial managers to vote against collegiality. The ballot, however, had about a dozen propositions, so to play it safe some bishops voted no to everything. When the balloting results were announced, it turned out that 90 bishops had voted against the infallibility of the pope, which sent the assembly into uproarious laughter. The main points of the collegiality schema passed easily. Another issue under serious debate was whether the Third Session of 1964 would be the final session of the Council. The present session was moving at a greater clip than the first two. There was considerable division on the question. For example, the Canadian bishops were in favor of wrapping up, while United States bishops as a rule favored another session in 1965. In the end, there was considerable anxiety that a fair number of schemas had not yet made the floor, most notably those on the Laity and another entitled “The Church in the Modern World.” Eventually the determination was made for a fourth session in 1965, and thus one of the Council’s most famous documents, Gaudium et Spes, “joy and hope,” would see the light of day and world-wide fame on the very last day of the Council. |

MORALITYArchives

June 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed