|

I missed last week’s Reformation post as I was participating in a diocesan educational event last weekend. So, getting back into the groove, I reread the post of two weeks ago and realized that I had not sufficiently explored the role of the papacy in the fourteenth century and on to the Reformation. I had pointed out that for the entire span of the 1300’s the papacy resembled nothing of what it is today. The century opened with the anti-French pope, Boniface VIII, issuing his controversial bull Unam Sanctam (1302) (from the Latin bulla, a lead seal applied to the end of a solemn papal pronouncement.) Unam Sanctam claimed ultimate authority over all peoples and things of the earth—including his intrusive enemy King Phillip IV of France.

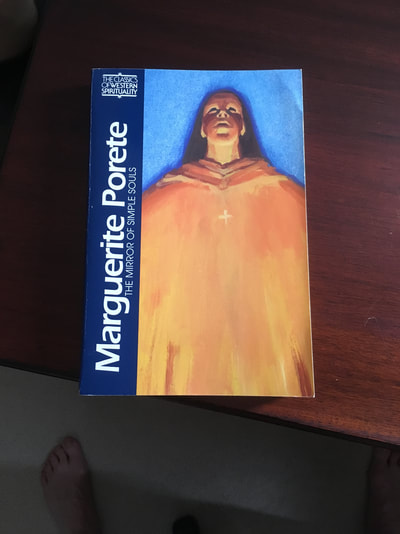

Phillip’s brief seizure of Boniface himself, which led to the pope’s imminent death, obviously gave pause to the cardinals who gathered in Rome to elect Boniface’s successor, Clement V, whose tenure as successor of St. Peter is probably one of the best narratives that no one knows. Clement was French (no surprise there) and was elected in conclave when Phillip appointed a number of French cardinals to swing the vote. Clement would soon “francophonize” the full college of cardinals, to borrow Kevin Madigan’s phrase, making it fully French and thus determinative of outcomes for the near future. Clement V did not renounce Unam Sanctam; for all practical purposes he simply passed it on to King Phillip, allowing him to exercise the unrestrained authority Boniface had claimed. I need to add a personal note here—I do not take pleasure in airing the dirty laundry of the Church; in fact, it disturbs me significantly. The theme of the Thursday post is the stream of events that led to a permanent division known today as the Reformation. One of the main divisions of the Reformation involves Church authority—its limits and, alas, its abuses over history. At the same time, the recovery of the Roman Catholic Church from its collective sins and its significant works of reform is one of the reasons I remain Catholic today. I also concur with the philosopher Santayana that those who ignore history are doomed to repeat it. That said, I must report that King Phillip ordered Pope Clement V to convoke the fifteenth ecumenical council of the Catholic Church, the Council of Vienne (1311-1312) for the express purpose of suppressing the Knights Templar. The Knights Templar was an independent religious order of knights which grew in wealth and influence from its founding in the First Crusade. History is divided on Phillip’s motives for destroying the Templars; he obviously sought their reputed wealth and would torture many knights to obtain it, but the existence of a free-standing militia—religion notwithstanding—would be a matter of concern for any monarch. The theological question is why a council was required for this dirty work in the first place. The most likely answer is that the Knights were independent and international in scope, and second to that, the Knights Templar were contrasted to another “safer” order at the time, the Knights Hospitaleers, which survives today as the Knights of St. John. The Council of Vienne was called to give “religious cover” to an overt act of aggression. Ironically, Vienne turned into a good example of why neither lawyers nor prosecutors like to take a case before a jury. As Wikipedia relates about Vienne, “a majority of the cardinals and nearly all the members of the commission believed the Order of Knights Templar should be granted the right to defend itself, and that no proof collected up to then was sufficient to condemn the order of the heresy of which it was accused by Philip's ministry…” The fathers of Vienne—most French at that—voted for due process in examination of the Knights for heresy. The Council then turned to a condemnation of heresy against the Beguines, a prolific cluster of mystics (mostly women) whose “crimes” seemed to be mobility and independent experiences of mysticism. Such groups were quite numerous in later medieval times. The most famous Beguine, Marguerite of Porete, was burned at the stake in 1311 but her work The Mirror of Simple Souls is popular to this day; I have a picture below of my own copy, available today from Paulist Press. Needless to say, Phillip IV was not happy with the Council’s deliberations on the Templars, and he pressured Clement to override the Council with his (Clement’s) own declarations authorizing full-scale interrogation and disbanding of all the Knights Templar throughout the Church. Clement settled in Avignon—after brief sojourns elsewhere--in the south of France after the Council. Southern France was somewhat more removed from political flux, and a return to Rome was probably not possible given the physical and political deterioration of the Eternal City. Clement did not expect the papacy to remain in Avignon forever. It was Benedict XII (r. 1334-1342) who reconciled the Church to an indefinite papacy in France. How did the Church respond to the relocation of the papacy to Avignon? As I wrote in the last post, the Christian citizenry had much to deal with during the century, and the effects of a relocated papacy did not much impact parochial life. What all levels of Catholics objected to was the pressure of papal taxes, with many suspecting that the money was actually enriching France. Those late in their taxes could be excommunicated. As Madigan writes, “The apostolic see of Peter had become an immense bureaucratic and fiscal machine. Once viewed as the leader of reform, the papacy came to be seen as the religious institution most in need of reform. Most thoughtful observers sincerely believed that reform could be accomplished only if the papacy returned to Rome. Among those advocating for a return of the pope to the Holy City was St. Catherine of Siena (1347-1380). In 1377 Pope Gregory returned to Rome, a move that was opposed by French Cardinals and different factions of the Roman body of Cardinals. Gregory did not feel safe in Rome and planned to return to France, but he died before he could leave Rome. The Romans quickly elected one of their own, Urban VI (r. 1378-1389), the first non-French pope in over fifty years. Urban proved to be a bit mad, and French cardinals, claiming intimidation, elected in a separate conclave Clement VII (anti-pope, 1378-1394). After attempting to seize Rome, Clement VII retreated to Avignon. Thus began “The Great Schism” of multiple popes, which would last forty years. Madigan comments that “the tragedy took on elements of farce when the Council of Pisa (1409), called to heal the Schism, created yet a third line of popes. The theological dilemma here was (and remains today) the question of who in the Church has the power to reform the papacy. In fact, two bodies did step forward to end the Schism, but having been rescued in this fashion, the Church today is cautious of these two institutions, and their work in restoring the papacy was a cause for significant discussion at Vatican II, six hundred years later.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Church HistoryArchives

February 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed