|

There are plenty of things that need fixing in the Catholic Church, but Thomas Day is the first commentator of my acquaintance to address the issue of liturgical music between hard covers. His first edition of Why Catholics Can’t Sing [1990] raised eyebrows at a time when perhaps the patient might have been saved. His 2013 edition featured here, concedes that the errors of the early days of liturgical music reform are so entrenched that those remaining brave souls who soldier on to Mass each Sunday are inured to leaders, texts, melodies, and accompaniments that systematically deny them their Baptismal right of participation specifically called for in Vatican II’s “Sacrosanctum Concilium,” the decree on the Sacred Liturgy.

Day’s 2013 edition recounts the Irish tradition of “secret, quiet Mass” rooted in the painful days of English suppression on the Emerald Isle. Expressive singing was the provenance of Protestants. Catholic immigration from Ireland formed the backbone of mainstream church custom in the United States, particularly in the big cities, and that reserved devotional style of Mass participation survived Vatican II and, in many ways, colors our congregational behavior to this day. [If Day undertakes a third edition, he may wish to contrast the natural musical freedom of growing Hispanic and Afro-American Catholic congregations which are not beholden to Anglo-Irish history and experience.] Vatican II’s “Sacrosanctum Concilium” called for skillful merging of the rich tradition of the Latin heritage with adaptations that would make for possible greater participation of the faithful, who frankly had little experience of this. The author notes a certain arrogance among many post-Conciliar American reformers who belittled the traditional pious sensitivities of Catholics as backward [his anecdote of the resistant old woman who refused to participate in the Kiss of Peace with a firm “I don’t believe in that s---“ is priceless. (p. 5)] Moreover, the self-induced pressure to “get the congregations singing” led to a grassroots development of new English hymnody “in tune with the times.” The first decade or so is remembered as the “guitar Mass” era which, as Day observes, was often relegated to the church basement or off hours by nervous pastors. The second wave draws more of the author’s critical energy. The peppy strums of Ray Repp’s 1960’s “Sons of God” gave way in the 1970’s and 1980’s to what I call the “John Denver” era, or what more people would refer to as the age of “The St. Louis Jesuits,” a representative group of the time. In Day’s assessment, this second wave of music became embedded as the permanent template of liturgical hymnody to this day. As a friend of mine put it, you still cannot go to an ordination without hearing “Here I Am, Lord.” Day has several major critiques of that era’s product. The first is its orientation toward performance—its creators did, in fact, become “stars” in the Church music world. Second, the music product was/is often unsingable for a typical congregation—it is verbose, complicated, and inconsiderate of average range. There is not a man alive who can sing “I Will Raise Him Up.” And it requires the impediments of bulky hymnals and progressive lens glasses--or NBA arena style jumbotrons. The third critique involves the identity of the pastoral musicians ministry as a whole. Day is in step with the American bishops’ “Sing to the Lord: Music in Divine Worship” [2007], one of the finest documents to come out of the USCCB. Both Day and the bishops concur that the function of cantors, choirs, and musical instruments is, at the most, to assist the congregation to begin singing, and then to melt into the congregational event. It is rare to see this process unfold correctly, because in truth there is extraordinarily little congregational singing to melt into. Have you ever wondered what your church would sound like if someone suddenly pulled the plug on the microphones and the organ during a song? If my memory serves me, Day’s 2013 critique is more inclusive of the entire liturgy, highlighting those factors which break the mood of the common Eucharist, or as he puts it, the unity of the sacred “dance.” Is it necessary, for example, for the celebrant to say “Good morning, folks” after the opening hymn and sign of the cross? He raises questions about the atmospherics of too much artificial lighting and carpeting which absorbs the sound of congregational singing. In a different key, Day pays more attention to the liturgical publishing houses and their influence upon local church music. If the goal of the liturgical renewal is common worship in song, it would stand to reason that [1] we need fewer hymns and more ways to sing the Mass parts themselves, and [2] our parishes’ repertoires ought to be small and familiar, eliminating the “book element.” Do we need hymnals with 750 selections? Not surprisingly, the author has numerous and thoughtful recommendations for a reform of the reform. Among others, he calls for a rejection of the common wisdom among musicians that the goal of church music is “to energize people and create spiritual excitement.” [p. 205] He calls for an abandonment of music which celebrates “the contemporary us” [p. 216], including a disturbingly large repertoire where the congregation is expected to sing in God’s voice, such as “Be Not Afraid.” [p. 73] He encourages fidelity to the Council’s priority that we sing the Mass itself [and avoid the pitfalls of the “four-hymn sandwich” format.] On this latter point, he is not afraid to introduce Gregorian Chant as well as antiphonal formats for singing the Gloria and Creed in English. And, a refreshingly novel thought, he reminds us that not every Sunday Mass need be a full musical showcase, recalling that years ago there was only one “high Mass” in every parish. Day’s 2013 edition obviously predates the Covid exodus. But his excellent analysis of liturgical music is even more potent today: will people return to Eucharist if their place at the table is not set? It will be sixty years next week, on the Feast of the Immaculate Conception, that the first of four sessions of Vatican II adjourned after a grueling two months of work. The formal close of the first session was overshadowed by the realization that Pope John XXIII, the pontiff who had called the Council back in 1959, was dying. The pope’s declining health was obvious to everyone. In attendance the Archbishop Karol Wojtyla, the future Pope John Paul II, observed “What was intended as au revoir turned into an adieu.” [p. 239] There was a certain degree of anxiety among the bishops about the future of the Council, as councils are automatically disbanded at the death of a pope until [or if] the next pope chooses to reconvene it.

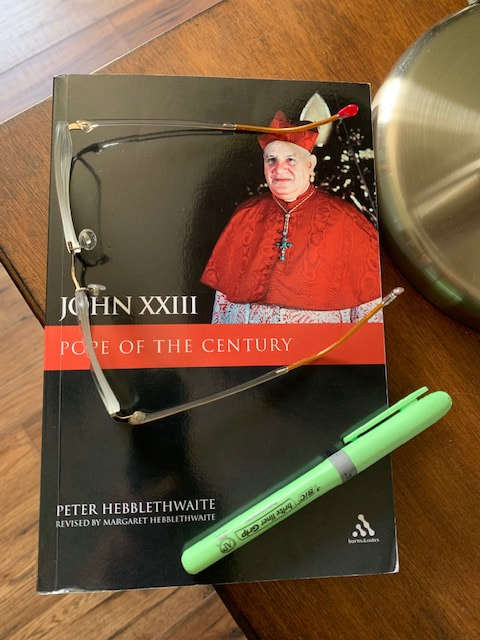

I strongly recommend John O’Malley’s What Happened at Vatican II [2008] for an excellent description of the preparation of the Council and the rejection of the presented agenda by the bishops in that first session of 1962. [See my Amazon review of O’Malley’s book here.] In brief, suffice to say that when Pope John established the various working committees to draw up the discussion drafts for the Council, he turned to the Roman Curial departments to organize and complete this work. The Roman Curia had responded quite negatively to the pope’s announcement of the Council in 1959, so it may seem surprising that the preparatory work for the Council was entrusted to men who were less than enthusiastic about it in the first place. In truth, the pope was limited in his options. The Curia was the only functioning bureaucracy in Catholicism capable of preparing for a council with a three-year deadline. In addition, Pope John was enough of a loyal traditionalist that he would not intentionally embarrass or diminish the reputations of men who had served the church for decades. And, at some level, he perhaps hoped to win their approval for the aggiornamento or winds of change he believed were permeating the Church through the Holy Spirit. The Curia recruited eight hundred persons to prepare the Council drafts, though as author Peter Hebblethwaite points out, many of the greatest theological minds in the Latin West were excluded for what we would call today “progressive methodology.” Among those excluded: Karl Rahner, Henri de Lubac, Jean Danielou, Marie-Dominique Chenu, Yves-Marie Congar, and the American priest-scholars John Courtney Murray and John L. McKenzie. What the Curia—operating in secret--could not control was the growing interest in the Council as discussed in the secular media and in popular writing, including the Swiss theologian Hans Kung’s The Council, Reform and Reunion. [1961] See America Magazine’s review of this work here. Kung’s book, eminently readable, shaped the possibilities of the upcoming council, particularly its implications for Catholic relations with other Christian Churches. Mainstream Protestant leaders became very interested in the possibilities of Vatican II. Pope John, it seems, was quietly pleased with the “outside rumblings” of Kung and other churchmen and worked behind the scenes to obtain a position of major importance for Father Austin Bea, S.J. on the newly created “Secretariat for Promoting Christian Unity,” which would have powerful influence later in the Council. In August 1962, two months before the opening of the Council, only seven drafts of conciliar documents were ready for dispatch to the world’s bishops. Four of these would be rejected outright on the floor of the Council. It was becoming clearer, to insiders at least, that the first business of the Council would be control of the agenda. On Sunday, September 23, 1962, Pope John was informed by his physician that his stomach cancer had progressed to the point that he was living on borrowed time. He decided to keep this prognosis secret, particularly in view of the Council, and he devoted much of his pre-Council work to negotiations with Communist governments to allow bishops behind the Iron Curtain [including Karol Wojtyla] to attend Vatican II. Finally, on October 11, the solemn opening of the Council was highlighted by the most important sermon ever delivered by John XXIII, on the purpose of the Council. [Sadly, it was also his last major address as his illness was advancing.] I take the liberty to quote his address at some length: The manner in which sacred doctrine is spread, this having been established, it becomes clear how much is expected from the Council in regard to doctrine. That is, the Twenty-first Ecumenical Council, which will draw upon the effective and important wealth of juridical, liturgical, apostolic, and administrative experiences, wishes to transmit the doctrine, pure and integral, without any attenuation or distortion, which throughout twenty centuries, notwithstanding difficulties and contrasts, has become the common patrimony of men. It is a patrimony not well received by all, but always a rich treasure available to men of good will. Our duty is not only to guard this precious treasure, as if we were concerned only with antiquity, but to dedicate ourselves with an earnest will and without fear to that work which our era demands of us, pursuing thus the path which the Church has followed for twenty centuries. The salient point of this Council is not, therefore, a discussion of one article or another of the fundamental doctrine of the Church which has repeatedly been taught by the Fathers and by ancient and modern theologians, and which is presumed to be well known and familiar to all. For this a Council was not necessary. But from the renewed, serene, and tranquil adherence to all the teaching of the Church in its entirety and preciseness, as it still shines forth in the Acts of the Council of Trent and First Vatican Council, the Christian, Catholic, and apostolic spirit of the whole world expects a step forward toward a doctrinal penetration and a formation of consciousness in faithful and perfect conformity to the authentic doctrine, which, however, should be studied and expounded through the methods of research and through the literary forms of modern thought. The substance of the ancient doctrine of the deposit of faith is one thing, and the way in which it is presented is another. And it is the latter that must be taken into great consideration with patience if necessary, everything being measured in the forms and proportions of a Magisterium which is predominantly pastoral in character. [Emphasis mine.] Pope John’s charter for the Council is clear enough. Vatican II would not create new doctrines, new feasts, or radical departures from the corpus of Catholic Faith. In fact, this aspect of the mission here is articulated quite traditionally. The challenge to the Church was the need to reexamine the language and understanding of timeless revealed truth by the lights available in the twentieth century—with the hoped-for outcome that the Gospel of Jesus would become better grasped, greater loved, and devotedly followed. In the last sentence cited above, John calls for a “pastoral” style of engagement with Catholics and non-Catholics alike. Vatican II would have no condemnations; there would be no burnings at this council as actually happened at the Council of Constance in 1414 when the reformer Jan Hus was executed during that council’s proceedings. Again, I would direct you to a full source on the substance of Vatican II, such as the O’Malley text cited above, to get the full flavor and detail of the first session in particular, the session Pope John lived to see. In the space of two months the bishops were faced with the challenges of setting priorities, and operating procedures to set something of a level playing field vis-à-vis the packaged plan proposed by the Roman Curia, all of this undertaken in Latin, which few bishops outside the Curia could speak. One might call the Council the precursor of “Synodality” as we use the term in very recent years. During the first session Pope John received advice on the direction of the Council from Cardinal Giovanni Montini, who proposed an outline for discussion that proved to be strikingly close to what would unfold, except that the Council ran to four sessions instead of Montini’s projection of three. Montini advised that the first session should focus on the nature of the Church itself, a subject which included the exercise of papal authority and the nature of the ministry of bishops. [The pope-bishop dynamic was a continuation of Vatican I’s work, a council forced to adjourn prematurely due to the danger of war.] The second session, the cardinal proposed, would deal with the mission of the Church, and would include the reform of the Liturgy. The third session in this plan would discuss the Church’s relationship with “human groups,” a hint of what would become Gaudium et Spes. Interestingly, Montini’s correspondence here was not discovered until 1983, twenty years after the Council. Montini, incidentally, was elected to the Chair of Peter in June 1963, taking the name Pope Paul VI, and oversaw the final three sessions of the council. Pope John observed the proceedings with great interest, and never lost hope in the outcome of the Council though he had plenty of reason to do so. The first session promulgated or issued no documents, and bishops became increasingly aware that the Council would last several years. But as the first session ended, Pope John recorded this entry in his journal: “Brothers gathered from afar to get to know each other; they needed to look each other in the eye in order to understand each other’s heart; they needed time to describe their own experiences which reflected differences in the apostolate in most varied situations; they needed time to have thoughtful and useful exchanges on pastoral matters.” [p. 239] The first session ended in an “almost penitential” mood on December 8, 1963, as the pope’s declining health overshadowed other concerns and left some question as to whether a new pope would even reconvene the council. A thoughtful man to the end, the Pope’s farewell address at the end of the Council was addressed primarily to the conservatives of the Curia, who had endured a hard time of things as their planning and documents were discarded or significantly redrafted. It is little known in the United States that Pope John had been involved in working toward the settlement of the Cuban Missile Crisis, which coincided with the first two weeks of the Council. Hebblethwaite believes that John Kennedy was reluctant to make this fact known because of his sensitivity over appearances of “taking orders from Rome,” a real issue in the 1960 presidential election. The likelihood of a nuclear holocaust led the dying pope to pen his most famous encyclical, Pacem in Terris [Peace on Earth], issued on April 11, 1963, just seven weeks before his death on June 3. At the conclave that followed, Cardinal Montini, his close friend, was elected to succeed him on the sixth ballot. The Council resumed that fall. Pope John XXIII’s reign as pontiff lasted less than five years, and it is most remembered for the Council he convoked, Vatican II [1962-1965]. One of the ironies of John’s life is that he lived only through the first session, 1962, and died of stomach cancer before the second session in 1963. More than that, the only session he lived to see produced not one of the sixteen documents that comprise the corpus of Council’s teaching. And yet, before he died, he navigated the three-year planning and the operation of the first session—admittedly in trial-and-error fashion—and carried forth the Council when many were working against it and others doubted whether it was even possible.

No one from the last Council, Vatican I [1869-1870], was alive when John announced the future Vatican II. He was aware that Pope Pius XII had considered a council during the late 1940’s, to condemn errors and proclaim the Doctrine of the Assumption of Mary; Pius decided against a council by condemning the errors in his encyclical Humani Generis [1950] and he declared the Assumption a dogma through his own infallible office. John was not certain precisely what shape his council would take, but his biographer Peter Hebblethwaite is clear that he did not want a Pius XII-style affair. “He expressed this by saying that its purpose was ‘pastoral.’ This meant it would not be primarily concerned with doctrinal questions but with the new needs of the Church and the world.” [p. 159] If the Roman Curia was sullen to the idea, the pope’s discussions with cardinals at the conclave and elsewhere convinced him that a pastoral direction might be well received. One of the enduring myths of Vatican II is that John’s call for a council was hijacked by European liberal theologians and bishops which led to a radical outcome never intended by John. This interpretation is an aberration drawn from several realities. First, in the Western Latin Church the only outstanding schools of theology were in Western Europe. [Catholic scholarship in the U.S. was languishing and smarting from the now-famous critique of Monsignor John Tracy Ellis in 1955.] Second, Europe had experienced the full fury of two World Wars and the disillusionment with parochial Catholicism that followed. A further consideration is that despite his desire for a pastoral council, John turned the preparation of the council’s agenda over to the Curia. Moreover, John seemed content to let major spokesmen from among the Curia explicitly define the philosophy and shape of the coming council. Cardinal Domenico Tardini in particular was not averse to taking the lecture circuit and press conferences [a new format for Vatican affairs] to make clear that he was not interested in ecumenism nor in “learning from the world.” [p. 171] From his journal and private conversations, it can be drawn that John was not overly upset by his argumentative “barons of the Church,” looking upon them as well-intentioned if not querulous uncles. He hoped to win them over despite the local jokes about the operation of the Vatican, that one official reigns, another spies, another keeps watch, another governs. And John merely blesses.” [p. 175] The Synod of Rome consumed much of the pope’s time in 1959. Predictably the Roman Curial cardinals considered this synod [discretely] a waste of time. Even those enthused about the Council, due to start in 1962, were perplexed about the timing of this local Roman affair. Many theories have been put forward about its purpose—one of the more ludicrous being that the pope called this synod as a sop to keep the curial cardinals occupied while Vatican II was under preparation. But here is another example of underestimating this pope. John, the student of history, recalled that the Council of Trent [1545-1563] had called for local synods as the means of reforming the spiritual lives of the faithful and the clergy. In fact, many dioceses throughout Italy had held synods over the centuries; Rome had not. John convoked the Roman synod at the city’s mother church, St. John Lateran. Unfortunately, the event itself was such a dud—a reading of canonical minutiae [priests were never to be alone with a woman, the racetrack was out-of-bounds for clerics, etc.]—that, if nothing else, it lowered the bar of expectations for the council. The pope consoled himself with the thought that “nothing is perfect in this world.” [p. 179] With Curia leaders dragging out the preparations for the Council and lowering expectations, the pope was not about to get exercised about the stalemate. But equally true, he was not going to squelch the enthusiasms for the future Council from outside Rome, either as prominent bishops and theologians began to weigh in, both on the style of the Council itself and the matters it would tend to. No theologian saw a greater window of opportunity than Hans Kung, a brilliant and youthful priest from Sursee, Switzerland and professor at the University of Tubingen [Germany] at the age of thirty-two. Kung, who had the good fortune of completing his doctoral dissertation just a few years before the Council about justification and the Christian Churches, grasped the ecumenical possibilities of the Council, intuiting the Pope John shared similar concerns for the unity of Christendom. Kung’s research had immersed him into the workings of the Council of Trent [1545-63], again connecting to one of the Pope’s own considerable historical interests. Among his findings Kung discovered that there was no one standard formula for conducting a council, and that the future Vatican II ought to take whatever form necessary to assist the Church. Most noteworthy in terms of public relations impact was Kung’s book entitled The Council, Reform, and Reunion [1960]. In this book Kung argued that Trent has been a reform council upon which the twentieth century Catholic Church could build, and he provided seven reforms that the Council could undertake that would, among other things, bring greater union with all the Christian Churches. All seven points were eventually embodied in the final decrees of Vatican II. Kung was hardly the first theologian to speculate on the Council—liturgical studies utilized by the Council dated back as far as the 1920’s—but Kung’s book, published jointly in English by Sheed and Ward, and Doubleday, appeared as a simple, straightforward paperback in multiple languages in the early 1960’s. It was the first book on the Council to appear in neighborhood American bookstores and to introduce the Catholic population—lay and cleric—to the possibilities of a “council,” a term which did not even appear in the standard Baltimore Catechism that I studied in the 1950’s. Scholars here in the United States, for example, reviewed this book in Catholic publications. Kung himself—who spoke multiple languages--became both a media figure and a lecturer in high demand. The Curia, working in secret on a council template with limited collegial discussion, was outraged. Pope John himself never publicly commented on the book. But he personally invited Kung to serve as a peritus [theological expert] for the Council before it opened; Kung recommended to the pope his professorial colleague who would also make major contributions—Father Joseph Ratzinger, the future Pope Benedict XVI. In the years leading up to the Council, it was now reasonably safe for leading scholars and church leaders to publicly discuss and advocate for issue to be addressed, regardless of what the Curia might put forward at the opening of the Council. Pope John’s biographer Peter Hebblethwaite devotes an entire chapter to the role of the Jesuit scholar Augustin Bea and his personal impact upon the pontiff. [pp. 190-198] Augustin Bea is one of the most remarkable men produced by the Church in the twentieth century. If you have the time, his biography here is worthy of review. Bea was nearly eighty during the planning years of the Council. A Jesuit priest, biblical scholar, and confessor to the late Pope Pius XII, Bea was one of those men who engendered trust on both sides of disputed issues. And so, it came to be that when the thorny issue of ecumenism arose in the planning stages, the pope approved a special commission headed by Bea to make commendations. In Hebblethwaite’s words, “Did he [Pope John] realize he had just made the most important appointment of his pontificate?” [p. 194] Later the pope would call it one of his “silent inspirations of the Lord.” No doubt assisted by Bea, Pope John established The Secretariat for Christian Unity, a branch of the Vatican bureaucracy that would be devoted to improving relations with separated Christians. Recall that the general principle of “outside the Church there was no salvation” was still entrenched in the minds of some Catholics. The more common and pastoral understanding in 1960 was that Protestantism [and non-Christian religions] lived in a defective relationship in separation from the one, true Catholic Church. Thus, the idea of an official branch of Catholic governance devoted to relations with other Christian Churches was a truly inspired innovation, a kind of “anti-Inquisition” if you will. Hebblethwaite writes that “John had always known that Vatican II would not be a council of reunion” in the sense of medieval councils such as Lyons and Florence. Bea stated the pope’s intention clearly: “The Holy Father hopes that the forthcoming Council may be a kind of invitation to our separated brethren, by letting them see, in its day-to-day proceedings, the sincerity, love and concord which prevail in the Catholic Church. So, we may say, rather, that the Council should make an indirect contribution to union, breaking the ground in a long-term policy of preparation for unity….” [p. 195] Bea, by breaking the ecumenical ice, influenced multiple documents of the Council, and collaborated intimately with Pope John during the first session, though this position did not spare him the consistent enmity and surveillance of Cardinal Ottaviani of the Holy Office. The pope let them duke it out hoping for a Hegelian synthetic compromise. This did not happen, and Bea would have to wait until the Council was in full force to see his work vindicated. In December 1960 Pope John received Doctor Geoffrey Fisher, the [Anglican] Archbishop of Canterbury at the Vatican, albeit discretely. Hebblethwaite: “The Curia was hostile to this hob-nobbing with ‘dissidents.’” [p. 197] And Fisher did his best imitation of an archbishop behaving poorly, using his time in Rome to address Anglican audiences on Catholic paternalism and other faults. With one year left to prepare for the Council, Pope John turned eighty, and as his biographer observes, he was growing more confident in his papacy and entered discussions on thorny practical details of Vatican II. Not all these matters were, strictly speaking, theological in nature. [In his outstanding history of the Council, What Happened at Vatican II (2008), John O’Malley describes the shortage of bathrooms, smoking areas, and coffee bars in Saint Peter’s. See my review on the book’s Amazon site.] In his address to the Central [planning] Commission in June 1961, Pope John reviewed many of these practical matters of the Council at considerable length. For example, the role of the periti or theological experts was considered, as well as the voting procedures and the rules of debate. On this matter of floor debate, the Curia determined that all discussions of the Council would be conducted in Latin. Stop and think about this linguistic conundrum. Four years of complicated theological debate conducted in a language that, truth be told, very few bishops had mastered to the point of being conversational. In fact, during the first session of the Council, Cardinal Cushing of Boston famously uttered “In Latin I represent the Church of silence.” [p. 199] Cushing offered to pay for a simulcast translation in multiple languages—United Nations style--for the participants of the Council, but the Curia rejected his offer, preferring to keep participants at a disadvantage. Cushing, in a huff, went home and boycotted the Council for a year. But this was in the distant future. Speaking of Latin, one of Pope John’s most ineffectual documents of his papacy, according to Hebblethwaite, was his Veterum Sapientia on February 22, 1962. The document reimposed the use of Latin as the teaching medium of philosophy and theology in major seminaries. There has been much speculation about why he issued this teaching when he did. Hebblethwaite suggests that since the Council floor meetings would be in Latin, it did not seem unreasonable to the Pope that priests and bishops of the future ought to at least be able to read it fluently. While John was a devout reader of Latin sources, his conversational fluency was so minimal that he practiced twice a day with a Vatican official prior to the Council. Those seminaries that tried to observe Veterum Sapientia gave it up at the end of the semester. [p. 207] One theory has it that the liturgical planning council was considering a renewal of the Mass at least partly in the vernacular, and that the Curia prompted John to push the brakes on what could be a potential runaway train by reinstating Latin in seminaries. The Pope expressed interest in the manner that the Council would be covered by the press and the electric media. He issued a directive that “nothing which helps souls should be hidden. But in dealing with grave and serious matters, we have the duty to present them with prudence and simplicity, neither flattering vague curiosity nor indulging in the temptation of polemics.” [p. 200] As Hebblethwaite observes, this was an ambivalent directive at best, and the Curia was quick to interpret the directive as meaning all issues of the Council were “grave and serious matters” and thus, in the planning stage it was understood that the Council would be conducted in secreto. [No translation necessary.] However, one of the periti of the Council, whom we now know to be a Redemptorist American priest, entered a contractual agreement to report on the Council for the secular New Yorker Magazine for reports from the Council. Under the pseudonym “Xavier Rynne,” the American public—and much of the world—got a continuous commentary on the progress—or lack thereof—of the conciliar debates and the politics of the assembly. [See my review of Rynne’s Vatican II here.] On his eightieth birthday the Pope received greetings from Russia’s Nikita Khrushchev. Unbeknownst to most of the world, John was quietly cultivating a relationship with Russia through the Italian Socialist Party. The Pope was not a Socialist, but rather, as his pontificate progressed, he became much more worried about war and peace, particularly in the nuclear milieu. Historians cite his involvement in the settlement of the Cuban Missile Crisis in 1962. He would write his most famous encyclical, Pacem in Terris [“Peace on Earth”] in April 1963, two months before his death. In November 1961, a general meeting of the planning board of the Council was convened. Composed of curial officials, senior bishops, and a sprinkling of periti, the body was tightly controlled by Cardinal Alfredo Ottaviani, Prefect of the Vatican’s Holy Office. There was considerable grumbling when Ottaviani revealed his blueprint for the council; he called for a new “Profession of Faith” that would repeat the anti-Modernist oath [of Pope Pius IX], repudiation of the errors of “the new theology,” affirmation of the difference between priests and laity, and denunciation of those who “spoke with exaggerated emphasis about the Church’s guilt and sinfulness.” [p. 206] In truth, this agenda could have been submitted in 1860 with virtually no change, which led the visiting planning bishops to ask, “so why are we meeting at all?” Ottaviani’s blueprint did not sound very much like the Pope’s call for aggiornamento, “opening the windows for fresh air.” The United States bishops’ representatives did not understand the Latin, either, and depended upon an elderly English cleric for summaries of the debates. Unknown to everyone on the eve of the Council were the results of a physical examination of September 23, 1962. Pope John was informed that stomach cancer—a scourge which had claimed several members of his family—was well-advanced and would claim his life in the not-too-distant future. The Pope did not reveal his condition publicly. But when asked what his role would be at Vatican II, he always answered the same way: “My role in the council is to suffer.” [p. 218] John XXIII: Pope of the Century by Peter Hebblethwaite--Part 5--The Highs and Lows of a New Papacy10/11/2022 Biographer Peter Hebblethwaite begins his narrative of Angelo Roncalli’s/Pope John XXIII’s papacy with a quote from Time Magazine published barely three weeks after his election on October 28, 1958: “If anyone expected Roncalli to be a mere caretaker Pope, providing a transition to the next reign, he destroyed the notion within minutes of his election…He stomped in boldly like the owner of the place, throwing open windows and moving furniture around.” [p. 144] Of course, his first matter of business was choosing his name. Only a Church historian could appreciate the humor in the fact that during the Great Schism there had been a John XXIII, a pseudo-pope of such poor character that the common wisdom held the name John to be unsuitable for any future pope. But Roncalli was a historian, too, and realized that the importance of the Apostle John should continue to be commemorated in the papal line, and indeed later in the century both John Paul I [r. 1978] and John Paul II [r. 1978-2005] would take the name of the Apostle ‘whom Jesus loved.” [p. 145]

Pope John appointed his secretary of state, Cardinal Domenico Tardini, the very next day. In truth, the two men were not particularly close, but the pope, who had not served in Rome since 1925 and did not know the inner workings of the Curia, wanted the counsel of an old hand. Hebblethwaite writes that the new pope was highly sensitive and respectful of the Curia, hoping to win their support for the reforms he had in mind, but added that “Later, Pope John would pay a painful price for this kid-gloved handling of the Curia; but as an opening move it was tactically shrewd.” [p. 147] Another early and interesting selection by the new pope was that of his confessor, and it became his practice to make a weekly confession at 3 PM on Friday, the hour of Christ’s death on the cross. Roncalli’s coronation lasted five hours, in part because he broke with custom and decided to preach. It was a groundbreaking homily, for in it the new pope said, in effect, that he was not going to imitate his predecessor as the master of all things. He described himself in these terms: “The new Pope, through the events and circumstances of his life, is like the son of Jacob who, meeting with his brothers, burst into tears and said, “I am Joseph, your brother.” [p. 150] It had been a great many years since any pontiff had identified his ministry in these terms. One might have to go back all the way to Saint Peter, and even then, only on the Apostle’s good days. By comparison, consider biographer Roland Hill’s account of the English Catholic layman Lord Acton’s audience with Pius IX just a century before: “He [Pius IX] leaned forward and gave us his hand to shake than merely to kiss, very gracefully and raised us up by it—without allowing us to kiss his red-shoed foot. He made us all sit down.” [Hill, p. 79] Pope John used his first days in office to introduce the idea “that a pope above all should be “pastoral.” One of the early groups to experience this fraternal outreach was the secular press corps. Two days after his coronation he met with the press for an informal conference, without prepared notes. He told the journalists that he had enjoyed reading their news coverage of how the world was responding to events in Rome. Then he added a truly funny aside when he said that was also reading their papers “to learn the secrets of the conclave.” Hebblethwaite notes that the pope’s friendliness and warmth won over the writers: “some tough-minded journalists admitted afterward and in private, to tears.” [p. 151] The pivotal decision by the new pope—and it was made early in his papacy—was the decision to call an ecumenical council, which would ultimately be named Vatican II. How the decision was made—and when it was made—is an intriguing narrative that different historians have treated in diverse ways. Hebblethwaite’s account is the most detailed. He reports that on the night before Roncalli’s election in the conclave, when it appeared that he would be elected pope, he was visited in his room by Cardinals Ruffini and Ottaviani, the latter the head of the Vatican’s Holy Office and arguably the most influential of the Curial Cardinals. Ruffini had suggested the idea of a council to the newly elected Pius XII in 1939, and twenty years later he made the same pitch to John XXIII. That Ottaviani—who proved to be one of the most oppositional forces in the unfolding of Vatican II—should be an inspiration for its calling is difficult to digest from our vantage point in history. However, it is very possible that Ottaviani had in mind the templates of at least the previous two councils—Trent [1545-1563] and Vatican I [1869-1870]—which solidified the doctrine and discipline of the Church. It turned out, however, that neither Ottaviani nor Ruffini knew the inner dispositions of the new pope and the kind of council he would endorse. Hebblethwaite quotes from the new pope’s diary Pope John’s encounters with cardinals from outside of Rome who came to pay their respects before departing for home. He heard “the expectations of the world and the good impression that the new Pope could make. I listened, noted everything down, and continued to wonder what to do—concretely and immediately.” [p. 157] It is extremely hard to know—even in our most private selves—when and how we make the pivotal decisions of our lives. So it may be that we will never know the precise moment that Pope John XXIII decided to call a council. If I had to guess, I would say that during his tenure as Patriarch of Venice, where he was a very active “peoples’ bishop” and rumors began to circulate that he was papabile, a “papal candidate,” so to speak, he must have begun to pray and reflect upon the kind of pope the world needed in the post-war nuclear era. It was truly a gift of the Spirit that the new pope came to decide that a new council should not follow the template of previous ones. As Hebblethwaite puts it, “Becoming pope had not magically endowed him with instant solutions for the universal Church. The best course would be to get all the bishops thinking about these problems together.” [p. 157] From the vantage point of history, Pope John’s council would be a true synod, a “walk together.” The new pope was acutely aware that time was not on his side. He celebrated his 77th birthday shortly after his election, and in reviewing the history of previous councils, he noted that Vatican I had taken six years to prepare. On the other hand, this was 1959 and not 1863, and travel and technology might facilitate preparation for a Council that, for all purposes, looked like a one-year session at most. However, time was the least of his problems, as he discovered on Sunday, January 25, when he assembled the nineteen curial cardinals to make his formal announcement. Frankly, the “rollout” at St. Paul’s Beyond the Walls was a mess. The pope attempted to do too many things and serve too many masters in making his announcement. The occasion was the final day of the Church Unity Octave, the eight-day annual novena of prayer for the reunion of the Church, an observance still celebrated today in Roman Catholicism. The day was chosen as a fitting backdrop to announce a council that, in the pope’s mind, would be a brotherly outreach to all peoples of good will. However, the content of the pope’s address was geared toward winning over the conservative cardinals. To reach them, he resorted to language they might understand and embrace. Hebblethwaite summarizes: “He still seemed to be using borrowed language when he went on to deplore the ‘lack of discipline and the loss of the old moral order’ which had, he claimed, reduced the Church’s capacity to deal with error. This pessimism about the present state of the world—sunk in error and in the grip of Satan—so contradicts Pope John’s usual attitudes that some explanation is called for. The simplest is that this address had one precise goal: to win over the cardinals to his project of a Council. To assist this process, he reflected the views he knew they held.” [p. 162] The pope complicated matters further by announcing three events at the same time: a council, a synod of the Diocese of Rome, and a revision of Canon Law. One could argue that the Rome Synod would serve as a “dry run” for the Council, though that was a stretch. The Code of Canon Law was revised—in 1983! —so there was hardly any urgency about the Code that should have distracted from the main agenda, the ecumenical council. As is well documented by historians, the cardinals received the news in cold, sullen silence. Pope John was bitterly disappointed at the response. In his car on the way back to the Vatican he said to his companion, “It’s not a matter of my personal feelings. We are embarked on the will of the Lord…Now I need silence and recollection. I feel tired of everyone, of everything.” [p. 163] The ultimate “downer” of the day was its coverage in the press. L’Osservatore Romano, the daily Vatican paper, ran the pope’s grim, anti-Communism reflections to the cardinals on the front page, and buried the announcement of the council on the inside. The good news—though it was not yet visible or widely appreciated—was the reality that many bishops and theologians, particularly in Europe, understood both the pope’s vision and the need for a council of hope and healing. In the coming days they would not let him down. On November 14, 1952, Angelo Roncalli, the Vatican Nuncio to France, received a private correspondence from Pope Pius XII asking if he was prepared to succeed the patriarch [archbishop] of Venice in the event of his death, which was believed to be imminent. It appears from Roncalli’s private correspondence that an appointment to Venice was one assignment he would certainly enjoy. Dating back to 1925 and his troubles with Mussolini and Pope Pius XI during the negotiations of a Concordat between the Vatican and Mussolini’s fascist state—an arrangement Roncalli publicly criticized—the former Vatican bureaucrat had been exiled to some of the most difficult Vatican posts in Europe, complicated by the rise of Nazi Germany and the horrors of World War II and its aftermath, including the descent of the Iron Curtain. Consider his diplomatic career to this point—Bulgaria, Turkey, Greece, and France. And while it is hard to resist the charms of Paris in the springtime, Roncalli’s time with “the Daughter of the Church” was marked by a long and acerbic recovery between those French who submitted to the Petain [occupation] regime and the resistance movement identified forcefully in the persona of Charles de Gaulle.

A few weeks later Pius XII announced a consistory of cardinals at which 24 new candidates would receive the red hat, including Roncalli. This was not exactly a blessing for Roncalli—if the sitting patriarch of Venice survived a few years longer, “Cardinal Roncalli” would have been assigned to the Curia, a place where he was little known and generally considered a lightweight. But on December 29, 1952, Roncalli read in his morning paper that the Venetian Patriarch had died, and he would thus be sending his luggage to Venice and not to Rome. Privately, he was delighted. It is worthwhile here to pause and examine the Consistory of Cardinals conducted on January 12, 1953. As Roncalli’s biographer Peter Hebblethwaite observes, “Though no one realized it at the time, it completed the college that would elect [Pius XII’s] successor, and therefore the next pope was somewhere among their number.” [p. 117] Consequently, as no more cardinals were added to the college before Pius XII’s death, and several deaths and detentions in Iron Curtain countries cut into the 1953 number, the conclave that would elect Pius XII’s successor would prove to be ridiculously small by today’s number, 53, if one can imagine that. In today’s math, 130 cardinals are eligible to vote; if the relatively modern rule of not voting past eighty is not considered, 226 cardinals could vote. In the back of his mind Angelo Roncalli realized that, as a cardinal, he was a hypothetical candidate for the papacy. It did not seem to be a preoccupation except in 1954, for Pius XII’s health was a major concern, at least among those in the know, and it is now known that the pope subjected himself to radical and experimental treatments that kept him alive until 1958. Pope Leo X [r. 1513-1521] is quoted as saying “God hath given us the papacy; therefore, let us enjoy it.” The new patriarch Roncalli was hardly this crass, but of all his assignments, his years in Venice were clearly his happiest. Again, recall that Roncalli was an excellent researcher and historian. He understood that Venice, once a true world power, began her fall when Portugal’s Vasco de Gama and Spain’s Christopher Columbus established trade routes that bypassed this military and economic giant in the fifteenth century. Hebblethwaite summarizes Roncalli’s thoughts of Venice: “Now it had crumbling palaces and pockets of poverty. It came to life in its festivals—of cinema, painting, and music—when it provided a picturesque décor for international jetsetters. In the summer it was crowded out with tourists, artists, and nouveaux riches. But the population of this historic city was declining as the young looked for work in Marghera and Mestre, by now large industrial towns…as patriarch he saw another Venice that the tourist posters preferred to ignore.” [p. 118] Ironically, I was in Venice earlier this year and my tour guide described the city almost verbatim except to note that in a few years Venice’s population would fall below 30,000 and would be no longer tenable as a city, and more as a Disney-like showcase with limited access. Patriarch Roncalli struck a happy medium for a proud city facing many problems from the very start. He permitted the custom of the parade of boats through the main canals on the day of his installation and immediately became a highly visible part of the city’s life. He enjoyed taking the vaporetto, the “water bus,” much to the chagrin of his chauffeur. He wanted to know his city from the ground up, and as Christmas approached, he involved himself in assisting the “migrant workers” or those who returned to Venice after working elsewhere most of the year. “I am like the mother of a poor family who is entrusted with so many children.” [p. 118] As a historian he endeared himself to the city with his interests in restorations and cultural events, including the restoration of the Benedictine Abbey on the island of San Giorgio, across the bay from St. Mark’s Cathedral. He met regularly with the full range of city officials, blessing the soccer teams and the new tankers. But it may have been a 1954 address on the silver anniversary of Mussolini’s Concordat with the Vatican that earned him a measure of national and ecclesiastical recognition. Mussolini’s recognition of the Vatican State—despite every grim event to follow—held a near sacred status among traditional Catholics in Italy and certainly in the Vatican. Roncalli, who had never bought into the cult of Mussolini, concluded his remarks deftly on Mussolini and the Lateran Pact: “So we have to entrust this humbled soul [Mussolini] to the mystery of divine mercy which sometimes chooses vessels of clay for the realization of its plans, and then breaks them, as though they had been made for this purpose alone.” [p. 122] Roncalli’s assessment of Mussolini and the Lateran Pact of 1929 served, as Hebblethwaite puts it, “more like a healing of the Italian national psyche.” And it certainly proved the career diplomat and archbishop could navigate difficult waters. Did Roncalli himself, or others in the Church, begin to consider him a papabile, a candidate for the papacy? It is an interesting question, because Pius XII’s health issues became known throughout the Church and the universal observance of the Marian Year. As general speculation of a papal election conclave circulated that year, Roncalli confided that a conclave would interfere with his plans for a pastoral visitation of his parishes followed by a Synod of his diocese. However, the fiftieth anniversary of his ordination fell on August 10, 1954, and Roncalli revealed a rarely seen temper at plans to celebrate the day with fanfare. As Hebblethwaite puts it, “One reason he wanted to lie low for his golden jubilee celebration was that gossip and speculation continued to present him as eminently papabile.” [125] Pius XII did not die in 1954, and exercised his energy by “sacking” Giovanni Montini, Vatican Secretary of State, by naming him Archbishop of Milan. Montini was one of Roncalli’s closest friends, and in 1963 Montini would succeed Roncalli as Pope Paul VI. But that was far off in the future. In the moment it was a reminder that ecclesiastic authority was cursed with a paternalism and ruthlessness that wounded those who served and revered the Church. Privately Roncalli had thought that Montini would succeed Pius XII though the latter had deliberately withheld the red hat from his secretary of state. Historians believe the actual reason for Montini’s “demotion” was his perceived openness to leftist influences [including the Catholic novelist Graham Greene!] Pius managed to live for four more years, during which Roncalli attended to a wide range of pastoral interests in his home diocese, including the lay apostolate and ecumenism. In 1957 he conducted a synod of the archdiocese of Venice in which he used the term aggiornamento [Italian, “bringing up to date”] for the first time. It would be a mistake to compare the operations of a 1957 Venetian synod to the wide-open 2022 synodal model of Pope Francis, though great care had been given to provide for universal participation. But Roncalli spoke on all three days of the event on the theme of episcopal authority, specifically its excesses in authoritarianism and paternalism. A good bishop, in his view, invited collaboration with and from his flock. When Pius XII died on October 9, 1958, Roncalli was just short of 77 years old as he packed his bags for the ordeal of his first papal conclave—and conclaves, even today—are physical as well as emotional, political, and religious ordeals. Did he plan to come back to Venice? It is joked in Rome that the cardinal who enters a conclave as pope comes out a cardinal. Did Roncalli head to Rome as a dutiful cardinal or a hopeful papabile? It seems something of both. “Hopeful” is probably too strong a word. We must take the man at his word when the senior officer of the Election Conclave, Cardinal Eugene Tisserant [a librarian by profession] put the fateful question to Roncalli, after the deciding ballot, “Do you accept?” Roncalli, who had known the moment was coming for at least twenty-four hours, replied; “Listening to your voice, ‘I tremble and am seized with fear.’ But what I know of my poverty and smallness is enough to cover me with confusion. But seeing the sign of God’s will in the votes of my brother cardinals of the Holy Roman Church, I accept the decision they have made; I bow my head before the cup of bitterness and my shoulders before the yoke of the cross. On the Feast of Christ the King, we all sang: ‘The Lord is our judge, the Lord is our lawgiver, the Lord is our king; he will save us. [Isaiah 33:22]” [p. 144] The popular wisdom I was taught and read for years is that after the long and controversial reign of Pius XII [r. 1939-1958] the electors were seeking an uncontroversial caretaker pope of senior years to give the Church some breathing space to collect itself before regrouping to plan its way into the balance of the century. It is closer to the truth, in retrospect, to say that the electors did not want another Pius XII. For it seems that Pius’s papacy had exhausted them with encyclicals, new feasts, doctrines, holy years, liturgical changes, and the like at a time when Italy was still recovering from the terrors of World War II. When Roncalli arrived in Rome, one of the first pieces of advice he was given as a papabile was “no more new feasts.” Roncalli’s easy temperament and comfort with tradition would have been a welcomed reprieve. Roncalli’s election, in the popular telling, has always been greeted with surprise given his age. But consider that Pius XII had been lax about naming cardinals. One of the funniest lines in Hebblethwaite’s book involves a 1958 encounter before the Conclave between Roncalli and Cardinal Elia Della Costa, the archbishop of Florence, who told his friend he would be a good pope. Roncalli protested: “But I’m 76!” To which Della Costa responded, “That’s ten years younger than me.” [p. 134] The entire voting conclave flexed old. Pius was notoriously lax about maintaining the College of Cardinals. He held only two cardinal conclaves—appointments of new members—in twenty years, the last one in 1953 which included Roncalli himself as the new Cardinal/Patriarch of Venice. Pope Sixtus V [r. 1585-1590] capped the number of cardinals at 70, and Pius XII restored that number in 1953. But deaths took their toll. In 1958 only 53 cardinals voted in the critical papal election. [Cardinal Mooney of Detroit died on the way, and two Cardinals were held behind the Iron Curtain.] By contrast, there are currently 120 cardinals eligible to vote for the successor of Pope Francis as of this writing. Recall, too, that in Roncalli’s day [1958] only Italians were elected popes—the papacies of John Paul II [Poland], Benedict XVI [Germany] and Francis [Argentina] were still two decades and more down the road. In this 1953 conclave, ten of the twenty-four new cardinals were Italians—and eight of them were assigned to Vatican positions within Rome. Only Roncalli [Venice] and Siri [Genoa] lived and worked outside of Rome and thus had an opportunity to break from the pack, so to speak, to distinguish themselves, as Roncalli had with his national speech on Mussolini and the Lateran Pact. In other years Siri might have been the favorite, given his energy and brilliance. Siri was only 52 at the papal conclave but there was little appetite in 1958 for the election of a potential 30-year pope. He would run—unsuccessfully—in later conclaves. Roncalli’s strongest opponent would prove to be Cardinal Gregory Peter Agagianian. Agagianian was running as a “non-Italian pope,” citing his birth in Akhaltsikhe [Georgia, southern Russia] in 1895 and promoting his possibilities for the Church as an “Eastern pope.” Agagianian is the only candidate Roncalli disparaged [though subtly.] He observed to friends that the term “Eastern” was so broad as to be meaningless—do Indians think like Chinese, he mused. Moreover, wherever his birth, Agagianian was an ensconced Vatican bureaucrat of many years as head of the Propaganda of the Faith Office. He would not be exactly a breach of fresh Oriental air. Roncalli discretely made the rounds to the “kingmakers” throughout Rome during the weeks of Pius XII’s funeral and days of mourning, and he attended the interminable briefings for the electors. He discovered that the mood of the inner chambers of the Vatican was grim. Pius XII’s final years were marked by the excessive power of his personal attendant, Sister Pasqualina, and accusations of nepotism. Roncalli was so rattled by tales of Pius XII’s family entanglements that he gave strict orders to his relatives to avoid Rome at all costs whether he won the election or not. Hebblethwaite, writing in the 1980’s, probably did not have full access to sources for Sister Pasqualina, who appears to be treated more favorably in very recent biographies. Hebblethwaite does include something of a troubling metaphor of the farewell to Pius XII—a grim tale of how the dead pontiff’s body exploded inside his casket in front of the Church of St. John Lateran, the result of the pope having been poorly embalmed by an eye doctor. [p. 132] Roncalli found the full funeral experience ghastly. As much as the papal funeral troubled him, it was the growing prospect of his own election that gave him his own dark night of the soul. The powers that be were now asking him pointed questions—for example, would he bring back Montini from France and make him Vatican Secretary of State? The “correct” answer for election was no, and Roncalli gave assurances to that effect, to which he was faithful after his election. [He did award his old friend a red hat almost immediately after his election, however.] But one of the most misunderstood dynamics of this papal election is the discussion of a Church Council. Did the idea of a future council play any role in the papal election of 1958? Again, the popular narrative regarding the call to an ecumenical council is that the idea emanated from Roncalli after his election to the papacy, that he sprung it like a lightning bolt upon the curial cardinals in 1959, and that they hated the idea. But this may be a gross simplification based upon a later presumption of 1958 attitudes and outlooks. What we now know is that the idea of a council was at least a part of the puzzle of Roncalli’s election. Several sources—breaking the oath of secrecy—reported afterward on the dynamic of the eleven ballots cast in the conclave. In the early voting Roncalli ran two votes ahead of Agagianian but without the necessary majority. Agagianian lost support as voters turned to Cardinal Luigi Massala, Archpriest of the Basilica of St. John Lateran in Rome, a favorite of those who felt that Roncalli was not smart enough for the papal office. However, Roncalli held his own after two days. And here begins one of the most intriguing aspects of this conclave. On the evening of the second day of the voting, Roncalli received a visit from Cardinal Alfredo Ottaviani and Cardinal Ernesto Ruffini. History remembers Ottaviani as the conservative curial administrator who attempted to foil the will of the majority bishops at every turn during Vatican II. But here we see a different picture. During a 1968 interview, and a follow-up assertion in 1975, Ottaviani claims that he, and many other cardinals, told Roncalli that “we think we need to have a council.” [p. 142] Evidently these two curial giants—Ottaviani and Ruffini—believed that Roncalli’s election was safe when they made this proposal, and Ottaviani writes that Roncalli made the idea his own. Consequently, Roncalli was elected the following day. I first read Hebblethwaite’s description of these events with considerable skepticism. By 1968 the first published books and assessments of Vatican II were being devoured by an interested Catholic public [yes, there was such a thing at one time], and every one of those books most surely contained the dramatic account of the Cardinal Archbishop of Cologne, Josef Frings, who, in the course of a speech to the Council fathers on November 8, 1963, denounced the methods of Ottaviani’s Holy Office as “unsuitable for the times” and a “scandal.” It would not be surprising if Ottaviani was attempting a little revisionist history to preserve his good name in the next centuries of the Church’s annals. On the other hand, it may be that Ottaviani genuinely hoped for a council and extracted a promise from Roncalli to do for the Church what the latter had just completed in Venice, a reform synod. This makes sense if we remember that Ottaviani’s use of the word “council” [and certainly the word “reform”] would be colored by the two previous councils of the Church, Trent [1545-1563] and Vatican I [1870], Trent was a refutation of Protestant errors and a reform of the Church as institution. Vatican I was a refutation of the modern world and the infallible assertion of papal authority. For a powerful curial administrator like Ottaviani, what was there not to like about a new council to clean up modern errors? Ottaviani was too smart a man to spell out for Roncalli what a future council might look like—i.e., whose heads should be impaled on spikes. And Roncalli, more listener than asserter, probably made no specific promises regarding agenda or outcomes. In truth, the idea of a council had been brought up at least twice by previous popes after each World War. [If my analysis is correct, the great irony is that Pope John later allowed Ottaviani to oversee the initial working drafts of Vatican II. These drafts were strongly rejected by most bishops who took the Council into the direction we recognize today, probably in the direction John had hoped for in the beginning.] In any case, the next day, on the eleventh ballot, white smoke appeared from the chimney. The now former Patriarch of Venice would be known hereafter by a new name. “I will be called John.” After two decades of difficult diplomatic service in Vatican bureaucratic exile in Bulgaria, Turkey, and Greece, it is hard to imagine another post for the aging Vatican diplomat Angelo Roncalli more challenging than the first three. However, in December 1944 he was appointed papal nuncio to France under the most curious circumstances. Biographer Peter Hebblethwaite describes the assignment in considerable detail in his biography of Pope John XXIII [pp. 96ff]. I will do my best to summarize this intriguing turn of events.

In many ways Roncalli owed his appointment to Charles de Gaulle, the hero of French resistance during the Vichy collaboration with Nazi Germany. The D-Day Invasion of Normandy took place in June 1944, and with allied advances and the liberation of France clearly on the horizon, the day of internal reckoning was approaching for France, divided between the collaborators and the resistance. The Church was hardly exempt from such division to the point that in June 1944 de Gaulle met with Pope Pius XII to discuss the French situation. The French leader was particularly concerned that the current papal nuncio to France was cozy with the Vichy government, and de Gaulle demanded his replacement. Pius XII refused, at least until he learned that Russia was recognizing the newly constituted de Gaullist government and sending its own diplomat to France. Pius XII correctly viewed the major postwar threat to be totalitarian communism, and Russia’s aggressive diplomacy with de Gaulle’s resistance government was deeply disturbing to the pope. Fearful of ending up on the losing side, diplomatically, the Vatican selected a new candidate to serve as nuncio to France, but he turned down the offer for health reasons. The war had exhausted the pool of potential Vatican diplomats, and thus, the position went down the bench to Roncalli, a man almost forgotten in Rome and a total unknown to France. Hebblethwaite reports that Pius XII’s appointment of Roncalli, who was still regarded as nondescript in the inner circles of the Vatican, was thought by some as a sign of the pope’s displeasure with de Gaulle’s attitude and policies. Roncalli, now sixty-three, harbored no illusions about his new assignment and how it fell to him. He joked that “where horses are lacking, the donkeys trot along.” And yet, on January 1, 1945, it was Roncalli in his new position who announced to the French nation its formal recognition by the Vatican. Hebblethwaite summarizes the nuncio’s address in a way that describes Roncalli’s challenge: “…in the eyes of the Vatican the Vichy regime had been an aberration in which France had lost her liberty and her place among the nations. The quarrel about legitimacy was over: full and ungrudging recognition was given to the provisional [de Gaulle] government. At the same time there was a hint…that the work of purging should be carried out with restraint and without splitting the nation irrevocably.” [p. 99] In truth, the French Church was in serious trouble long before World War II and the Vichy government. Think back to the French Revolution [1789] and the rise of Napoleon, an era of strong backlash against crown and church. In the modern post Napoleonic era the Catholic Church in France was losing the loyalties of the “blue collar” population. So serious was the problem that in 1943 certain members of the French hierarchy—notably Cardinal Suhard--inaugurated what has become known as “The Worker Priest Movement.” To overcome the alienation of the working class—and their growing socialist sentiments—a small but intense number of French parish priests were released from parochial responsibilities to work side by side with laborers on the docks and in the factories, to earn credibility and demonstrate the Church’s interests in the pastoral and economic welfare of the common people. Pius XII called a halt to the experiment in the 1950’s when a number of the worker priests became political activists in Socialist parties, but the experiment demonstrates the old and new divisions in French society and in the Church—between the Vichy loyalists and the French resistance, for example, and the conservative rich and the struggling working class as another. France was Roncalli’s first assignment as a major diplomat with the full powers of the office. In Bulgaria, Turkey, and Greece, he had been a successful nuncio because Catholics were a minority of the population, and he could conduct his work in the style of the good pastor that he was instinctively. But in France, as he confided to a friend, he felt like he was “walking on live coals.’ [p. 100] The new French government called for the removal of “collaborationist bishops,” i.e., those bishops who acquiesced to the Vichy regime during World War II. The Interior Ministry provided the nuncio with a list of bishops whom it considered major collaborators, and another list of what it considered to be suitable replacements. Roncalli was hesitant to cooperate on the grounds that civil rulers were attempting to appoint bishops, a throwback to the “Lay Investiture Controversy” of the eleventh century, and he wondered aloud if the sitting bishops should be judged so harshly, given the fact that during the war, mistakenly or not, the Vichy government was considered the law of the land. His diplomatic counterpart contended that the continuing ministry of these collaborators was dividing Catholic laity and complicating the enormous challenge of social reunification of France, not to mention fueling a new wave of anticlericalism. In fairness, Roncalli had not been in France long enough to absorb these nuances—he spoke minimal French—and as nuncio he was Rome’s man in France, not vice versa. In the end, only a handful of bishops were quietly retired with pension, and the future pope found time to engage in his personal passion, historical research. During his early years in France Roncalli seemed uninvolved in a new wave of French theological scholarship and vitality which produced several of the personalities who would significantly impact Vatican II, including Yves Congar, Marie-Dominique Chenu, and Henri de Lubac. However, the era of 1945-1955 was not a congenial one for visionaries. Pius XII issued Humani Generis in 1950 in which he condemned “the new theology,” and that same year he declared the Assumption of the Virgin Mary a doctrine of the Church—which troubled scholars who argued that there is nothing in the Bible to justify the doctrine, all things considered. Many career theologians in France and elsewhere were silenced by the Church and/or forbidden to teach. [In the United States, the Jesuit scholar John Courtney Murray was silenced in 1954 for his writings on religious freedom and freedom of conscience.] Hebblethwaite’s biography underscores something of the mystery of Roncalli’s personal “working theology.” Those who knew him and worked with him in France found the nuncio hard to reconcile with his later persona as a progressive pope. The truth is that he was neither as conservative as he seemed in France nor as liberal as he seemed in his five years as pope. As a pastor at heart—and with a long record of successful pastoral ministry throughout his life—he was troubled by what he saw in France. In his journal he expresses “a certain disquiet concerning the real state of this ‘eldest daughter of the Church’ and some of her obvious failings. I am concerned about the practice of religion, the unresolved question of the schools, the lack of clergy, and the spread of secularism and communism. My plain duty in these matters may come down to a matter of how much and how far. But the Nuncio is unworthy to be considered the ear and the eye of Holy Church if he simply praises all he sees, including what is troublesome and wrong.” [p. 108] Roncalli was not an expert theologian, but he was a good historian. Roncalli certainly appreciated the fact that in his lifetime he had witnessed moral collapse of apocalyptic proportions—two world wars, the Holocaust. He might have been forgiven if he believed that after the defeats of Germany and Japan the Church might return to its status quo, which in fact was the prevailing consensus among institutional Church leaders at that time. But as his memoir indicates, he was troubled by the serious problems facing the Church in postwar France. Whether or not France’s “new theologians” influenced him is hard to say, more likely not so much. But Roncalli’s strength was not theology as much as “reading the streets;” it was the pastoral care of souls which shaped his thinking on the welfare of the Church. He was pained that his position in France did not give him much opportunity to exercise his preferred face-to-face pastoral ministry, but what he did see was enough to convince him that “the eldest daughter of the Church” was in grave difficulty, and if French Catholicism was ailing, it was likely that much of Western Catholicism was not much better off, even if Catholics in countries like the United States were not yet quite as aware of a weakening of their infrastructure. It is interesting that everything Roncalli confided to his journal about the malaise of 1947 French Catholicism can be applied to the Catholicism of 2022 in the United States. Roncalli would not remain in France long enough to solve its problems. In 1953, at age 73, he received what was thought to be his last Church appointment. He was named Cardinal by Pope Pius XII and sent to Venice as its Patriarch [Archbishop]. It is not too much of a stretch to call this last appointment Roncalli’s “gold watch” appointment for years of service to the diplomatic corps. He knew Venice well, as it was close to his birthplace, and he looked forward to a return to fulltime pastoral engagement. It was a good place to end a long and arduous career of pressure diplomacy. If Roncalli had died in Venice, he would have passed on as a happy man. But God had other plans. On February 17, 1925, at the age of 44, Monsignor Angelo Roncalli was sent into ecclesiastical exile for his outspoken discomfort with the growing power of Mussolini and the Fascist Right in Italy, at a time when the Vatican was attempting to work out a concordat or agreement with Mussolini. [The Concordat was completed in 1929.] Biographer Peter Hebblethwaite describes this era of Roncalli’s life as “Ten Hard Years in Bulgaria,” [pp. 55-69] though his next foreign assignments would be even more challenging. As you might imagine, there is an official record of Roncalli’s meeting with the Cardinal Vatican Secretary of State where the assignment was made. There is also Roncalli’s recollection given many years later, where he quotes the official’s advice: “I’m told the situation in Bulgaria is very confused. I can’t tell you in detail what is going on. But everyone seems to be fighting with everyone else, the Moslems with the Orthodox, the Greek Catholics with the Latins, and the Latins with each other. Can you go there and find out what is really happening?” [p. 55]